Structure and Post-Structure in Majora’s Mask

Posted on April 26 2013 by Legacy Staff

I’ve gone on the record as saying that Majora’s Mask is my favorite game of all-time. While that has changed recently (blame Bioshock Infinite), it remains one of my favorites and the single best game in the Zelda series by my vote. I could explain at great length the many reasons why that is, but what all of them boil down to is that the game is so wonderfully enigmatic, so incredibly intriguing in so many ways, that I can sit down and play the game with fresh eyes almost every time, seeing new things and having new ideas as I play through it.

I’ve gone on the record as saying that Majora’s Mask is my favorite game of all-time. While that has changed recently (blame Bioshock Infinite), it remains one of my favorites and the single best game in the Zelda series by my vote. I could explain at great length the many reasons why that is, but what all of them boil down to is that the game is so wonderfully enigmatic, so incredibly intriguing in so many ways, that I can sit down and play the game with fresh eyes almost every time, seeing new things and having new ideas as I play through it.

The last time I did this, it struck me that Majora’s Mask is a wonderful example of two opposing academic theories that spread across multiple fields: Structuralism and post-structuralism. What really intrigued me was the way the game tackled these theories: It constructs an elaborate structuralist frame through which it addresses post-structuralist themes, despite the fact that these two theories are usually always completely opposed to one another. Let’s examine these two theories and see how Majora’s Mask uses them to develop its themes.

Structuralism is a theory that grew out of linguistics writings during the early 20th century. At its most basic, it argues that human society and culture cannot be viewed as a set of components, but rather must be viewed in terms of their relationship to a larger structure that comprises all of society. It argues that the meaning of human actions and ideas exists only in terms of the way those actions and ideas interact with others. In short, it looks at the big picture — a web of interactions making up the whole — and not the smaller pieces that make up that larger picture.

Throughout the years this idea has been applied to artistic criticism techniques, and ultimately results in the concept of “grammar”. Linguistic grammar is of course rules that govern language use, but grammar in an art form refers to a set of artistic techniques that are commonly recognized to convey specific meanings. Let’s use film as an example: Certain techniques in film are understood to convey specific meanings not because they inherently have those meanings, but because of frequent use and reuse of certain techniques to convey them, and this grammar is agreed on and understood by those experienced with the medium. A low-angle shot of a character is agreed to mean that the character has a higher status, for example. We’ll revisit this concept a bit later with a focus on gaming grammar, but for now, just understand that structuralism argues for this creation of grammar, as grammar is a structure formed by the interactions between different works of art. The interactions are the reuses of techniques with specific meanings, and they form the grammar of the medium as those experienced with it come to recognize these meanings. Without the relationship between these different works of art, there would be no grammar and therefore no meaning.

In reaction to structuralism, a number of theorists began to argue against some of its key tenets. Several smaller branches of theory grew out of this movement, which has been called post-structuralism, but the one we’re going to focus on is called deconstruction. Like all schools of post-structural thought, deconstruction is a specific refutation of structuralist theory. It specifically rejects the structuralist idea of meaning emerging through interaction, as it states that the elements interacting are inherently defined by their interaction. This is easy to see at work in language. Take the term “house” for instance. If I were to say, “I live in a house,” you would have a reasonable mental image of what I live in. But if I were to say, “I live in a cabin, but my friend Jack lives in a house,” you would probably have a different image of Jack’s house than you did my house. That’s because of this idea that the meaning of individual elements — in this case the house and the cabin — depends on their interaction. Saying that I live in a cabin or a house alone means something different than if I say I live in one and Jack lives in the other; opposition changes the meaning of a word.

Now, deconstruction specifically attacks binary oppositions. Similar to the house/cabin example above, binary oppositions are pairs of words whose meaning is derived from their opposition to each other, but unlike the house/cabin example, these words are direct opposites. Good and evil. Light and dark. Up and down. Big and small. Deconstruction attacks these binary pairs specifically because binary opposition creates an unstable language base. The house/cabin opposition above is going to depend on the big and small binary: A house is bigger than a cabin, and a cabin is smaller than a house. But if you add another word in the mix — let’s say, shack — then suddenly big and small aren’t enough. You’re getting different images. That’s because, according to deconstruction theory, meaning is unstable when defined only by opposite or binary pairs; if meaning depends on interaction between elements as structuralists say, then they cannot be sorted into binaries because the meaning will change when the interaction changes, and so binaries are insufficient. Binary pairs are a critical part of the way that structuralists define interactions — the house and cabin being a great example — and subsequently the way that they understand the structure that those interactions create, so post-structuralists oppose structuralism because they believe interactions cannot be sorted into binaries.

This is an incredibly simplified version of both of these theories, and both of them have significant things to say about the nature of language, but for our purposes, this is enough of a basis with which to look at Majora’s Mask.

Structure: The Three-Day Cycle

Given the definition of structuralism that we’ve established, I’m sure many of you can pinpoint the primary structuralist element within Majora’s Mask: The three-day system that governs the entire game. This is my favorite aspect of Majora’s Mask because of the way that it constructs the world of Termina and makes it all feel connected: Every time that Link interacts with one of the game’s characters, he changes future events in that given cycle. If he talks to Anju, the innkeeper of the Stock Pot Inn in East Clock Town, between the hours of 1:50 and 4:00 PM on the First Day, he receives a Room Key. Shortly thereafter, a Goron with the same name as Link appears and finds that his reservation has been filled. From that point until the player resets the cycle, the Goron can be found sleeping outside the Stock Pot Inn. Had Link NOT spoken to Anju during those hours, he would not be sleeping outside, and presumably be in the room that Link is given access to.

Given the definition of structuralism that we’ve established, I’m sure many of you can pinpoint the primary structuralist element within Majora’s Mask: The three-day system that governs the entire game. This is my favorite aspect of Majora’s Mask because of the way that it constructs the world of Termina and makes it all feel connected: Every time that Link interacts with one of the game’s characters, he changes future events in that given cycle. If he talks to Anju, the innkeeper of the Stock Pot Inn in East Clock Town, between the hours of 1:50 and 4:00 PM on the First Day, he receives a Room Key. Shortly thereafter, a Goron with the same name as Link appears and finds that his reservation has been filled. From that point until the player resets the cycle, the Goron can be found sleeping outside the Stock Pot Inn. Had Link NOT spoken to Anju during those hours, he would not be sleeping outside, and presumably be in the room that Link is given access to.

This is a tremendously small event; a small detail in a massive game filled with much greater details. Bringing spring to the Mountain Village, clearing the poison in the Southern Swamp, clearing the waters of Great Bay and ending the curse in Ikana Canyon are all much, much larger acts that have tremendous effects on the other aspects of the world, opening access to new interactions with characters and new sidequests to pursue. To examine the meaning of these actions, we have to look at their effect on the whole.

For example, bringing spring to the Mountain Village intrinsically means that the cold that has been plaguing the Gorons is gone. But it also means that Link can be certified to carry Powder Kegs after a short training exercise involving opening the Goron Races. Opening the Goron Races allows Link, masquerading as Darmani, to enter them and potentially win the Gold Dust, which allows the smiths at the Mountain Village to forge his Razor Sword into a Gilded Sword, the best sword in the game. Bringing spring to the village by defeating Goht in Snowhead Temple has its own inherent benefits and meaning, but as part of the larger structure that is Termina, it has much greater meaning. This is the core of structuralism, and its presence in Majora’s Mask is a large contributor to the wealth of sidequests within the game.

But this is ultimately just the superficial mechanic of the game, and says nothing about the ultimate thematic purpose of the game. In fact, Majora’s Mask plays on this structuralist base to develop and explore themes that are decidedly post-structuralist.

Post-Structure: “Let’s Play Good Guys and Bad Guys”

Here at Zelda Dungeon, we’ve discussed the themes of Majora’s Mask a few times in the past. That discussion, however, has often focused on whether it qualifies as a “dark” game or not. I, however, argue that the themes of the game are neither dark nor light, but rather lie squarely between the two extremes. Ultimately, Majora’s Mask is a reflective experience that presents questions to the player, and invites them to consider these themes and come to their own conclusions. The primary way that the game does this is by exposing binaries and then tearing them down, in a decidedly post-structuralist act of introspection on the part of the player.

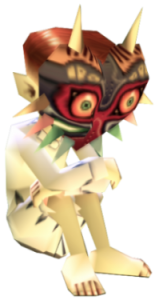

There are two primary binaries that I believe the game asks players to consider, if implicitly. The first of these is the traditional fantasy binary of hero and villain. Traditionally, these roles are applied to the protagonist and antagonist of a fantasy story respectively. But I argue that Majora’s Mask heavily blurs this line and tasks players with deciding what side of the line they fall on. In the final moments of the game, Link encounters five children living on the Moon, each of them wearing one of the masks of the five bosses throughout the game. The child wearing the Gyorg mask asks the following question (among others):

Shortly thereafter, the child wearing Majora’s Mask asks Link to play good guys and bad guys, and then assigns roles like so:

These questions are deliberately asked in such a way as to make the player question their role as a hero or a villain. In typical definitions of “hero” and “villain”, the question of doing the right thing is always critical to the definition. Heroes are usually defined as those who do the right thing for the benefit of others, and villains often as those who don’t, for their own benefit. So asking what the right thing is, as the Gyorg child does, is critical to this question of whether or not Link is a hero. Though it is far beyond me to be the arbiter of what is right and what is wrong, there are a few things that we can all agree upon as right and wrong (or at least I would certainly hope we could agree upon). Stealing is wrong, and helping those who are victims of theft is good! So when Link helps the Bomb Shop lady at midnight on the First Night by stopping Sakon from stealing her package, he has done a good thing.

But what about when Link uses time travel to cheat at the lottery? Isn’t cheating a bad thing to do? What about when he cheats at the Treasure Chest Shop game? Or, if we go more extreme, what about when he impersonates the dead? When he puts on the Deku, Goron, or Zora Masks, he takes on the appearance, and subsequently the identity, of the departed spirits who created the masks. He becomes the Deku Butler’s son — and gives the grieving father a flashback of him — whose whereabouts are unknown to him. Is this a morally right thing to do, to return these memories to a father who is so concerned about his son? What about appearing as Darmani, the departed hero of the Gorons, to the Elder’s son? Is giving him the false impression that, despite being assumed dead, his hero is in fact alive, only for the imposter hero to later disappear, a good thing to do? This same dilemma goes for Mikau, the Zora guitarist, still with no answer.

Are these good things that Link does? That’s ultimately left for the player to decide. But it is inarguable that he lies and cheats multiple times throughout the game, and all of it to get the Mask out of the hands of the Skull Kid. But even this act is shrouded in unclear motives. Is Link doing it out of altruism, to save the world, or out of a desire to clear his debt to the Happy Mask Salesman? Or perhaps even out of revenge? Why is Link doing all that he does?

These questions are critical to classifying Link as a hero or a villain. That classification is ultimately up to you, the player, but the fact remains that Link does a few things that are less than heroic throughout the game. Regardless of whether you classify him as a hero or a villain, the binary is broken down, because he is not purely either.

The other binary that the game examines and ultimately collapses is that of life and death. We’ve already brushed on this topic before: Link, through the Song of Healing and the transformation masks that result from the song, is able to effectively bring dead people back into the realm of the living. Even beyond that, their spirits linger, as seen in Ikana Canyon and in Snowhead (Darmani’s ghost). While there are absolute states of life and death within the game, there are also murky areas in between. There are those who cling to life despite having died, and those who manage to continue influencing the world despite their departure. By having Link interact with other people as if he were these departed characters, the game deals with the concept of “unfinished business” that is so popular in fiction, but in such a way that it examines the impact a single person can have on others (hey look! Structuralism peeking through!). This theme inherently involves the breaking down of the life and death binary.

The other binary that the game examines and ultimately collapses is that of life and death. We’ve already brushed on this topic before: Link, through the Song of Healing and the transformation masks that result from the song, is able to effectively bring dead people back into the realm of the living. Even beyond that, their spirits linger, as seen in Ikana Canyon and in Snowhead (Darmani’s ghost). While there are absolute states of life and death within the game, there are also murky areas in between. There are those who cling to life despite having died, and those who manage to continue influencing the world despite their departure. By having Link interact with other people as if he were these departed characters, the game deals with the concept of “unfinished business” that is so popular in fiction, but in such a way that it examines the impact a single person can have on others (hey look! Structuralism peeking through!). This theme inherently involves the breaking down of the life and death binary.

It’s interesting the way that these post-structural ideas arise so organically from a structural base. The two theories are diametrically opposed in most every other setting, but here they coexist rather nicely, and work in tandem to deliver some powerful thematic ideas.

One More Thing

There is just one other thing I’d like to discuss, and that is the way that Majora’s Mask subverts typical Zelda grammar.

Now, as we discussed earlier, structuralists argued for this concept of artistic grammar, a collective understanding of the way that certain techniques should be used to achieve an intended effect. This works in gaming as well as it does other art forms, and we can even limit it down to a grammar within the Zelda series exclusively. We’ve all noticed the way that with each Zelda game that we play, the next feels easier because we’re accustomed to all the tricks of the trade. We know the way that the game suggests solutions to some puzzles, and know what to look for when we get stuck. That’s because with each game, we become better versed in “Zelda grammar”; we spot certain similarities in dungeon design and know what those similarities imply. When we see small grooves in the ground that are just above ankle height, we know right away that there’s a block puzzle waiting for us. When we walk into a room that appears empty at first, but the door locks behind us as we enter, we know we’re in for a fight. All of these small, telling indicators of what is about to happen accumulate as we play multiple games in the series, and eventually we become so versed that we know what’s coming before it arrives.

Majora’s Mask is often cited as one of the, if not THE, hardest Zelda games (as a side note, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link is much more difficult by my vote, but for reasons of a challenging combat system rather than challenging puzzle design, which is what I am discussing here). This is precisely because the way the game is designed subverts Zelda grammar. In its dungeon design, which is often praised, it goes off the beaten path and delivers challenges uncharacteristic of the series.

Typical Zelda formula involves traversing a dungeon, finding an item, and then using that item to solve puzzles to complete the dungeon. Most of the dungeons in Majora’s Mask, however, subvert this formula by using primarily items the player already possesses, and using the item acquired within the dungeon simply as a way of opening new paths. The Fire Arrows in Snowhead Temple are most commonly used to melt ice blocks that are blocking doors. The Light Arrows in the Stone Tower Temple are most significantly used to flip the dungeon, allowing the player to access an inverted version that changes everything that came before and offers new challenges that are independent of the Light Arrows. These concepts are directly against typical Zelda grammar.

But the greatest subversion is the introduction of the transformation masks, which offer Link an entirely new ability set that is used for both combat and solving puzzles. There are no precedents for this gameplay mechanic elsewhere in the series (barring, perhaps, the Wolf Form of Twilight Princess), and as such there is no amount of awareness of Zelda grammar that can make players familiar with the masks and the gameplay surrounding them. Introducing this new mechanic, which was such a complete overhaul of the core gameplay of the series, utterly destroyed any chances of Zelda grammar awareness making the challenges easier and the puzzles more quickly solved.

But the greatest subversion is the introduction of the transformation masks, which offer Link an entirely new ability set that is used for both combat and solving puzzles. There are no precedents for this gameplay mechanic elsewhere in the series (barring, perhaps, the Wolf Form of Twilight Princess), and as such there is no amount of awareness of Zelda grammar that can make players familiar with the masks and the gameplay surrounding them. Introducing this new mechanic, which was such a complete overhaul of the core gameplay of the series, utterly destroyed any chances of Zelda grammar awareness making the challenges easier and the puzzles more quickly solved.

Conclusion

I really love Majora’s Mask, and I love it because it makes me think. It makes me think because it has a thematic depth to it that, when explored to its deepest reaches, can be rather daunting. It poses questions to which there are no clear answers, and indeed no comfortable answers. It tears down the typical fantasy binary of hero and villain, and blurs the line between life and death. It often ignores the grammar of the series, the conventions that make it feel familiar, and suddenly as a result the game is more challenging and invites you to think about new conventions as you play through the game.

There is a structural base to the game in the three-day cycle that lends it a rich narrative and character depth, with complex and intriguing interactions at play. But this structural base gives rise to the post-structural themes, themes that inspire thought and reflection. That’s more than can be said of most games, and it’s why I love this game as much as I do.