Looking Back at the Oracle of Ages Choose-Your-Own-Adventure Book

Posted on February 24 2021 by Rod Lloyd

I discovered The Legend of Zelda in 2001. While I had been first introduced to Link and the land of Hyrule through Super Smash Bros., my first true encounter with the series came with Majora’s Mask. I spent several sleepless nights playing through that game with a friend, and several sleepless nights more playing through Ocarina of Time. And once those adventures were concluded, I was ready for any, and I mean any, other Zelda experience that came my way.

Unfortunately for me, a kid with only a Nintendo 64 to his name, other Zelda titles were out of reach for the time being. But by the Goddesses’ divine graces, my Zelda appetite was satiated by a routine trip to the Scholastic Book Fair. As I perused shelves filled with fresh copies of Captain Underpants and I Spy, my gaze was drawn to a familiar elf boy with a green cap. There, on the covers of two distinctly colored paperback books, was Link, the Hylian hero I had come to know and love.

Scholastic’s Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons choose-your-own-adventure books were as formative to my Zelda fandom as the video games were. If not for them, I likely would not have sought out a Game Boy to the play the games they were based on, I would not have played Link’s Awakening DX shortly afterward, and I would have forgotten the Zelda series by the time The Wind Waker released. I owe quite a lot to those little books.

So, in honor of the 20th anniversary of not only the Oracle games’ release but of my relationship with the Zelda series in general, I wanted to look back at one of these choose-your-own-adventure titles to see how it holds up. And seeing as Ages is my personal favorite between the two Oracle games, I have decided to crack that book open and see what it has to offer all these years later.

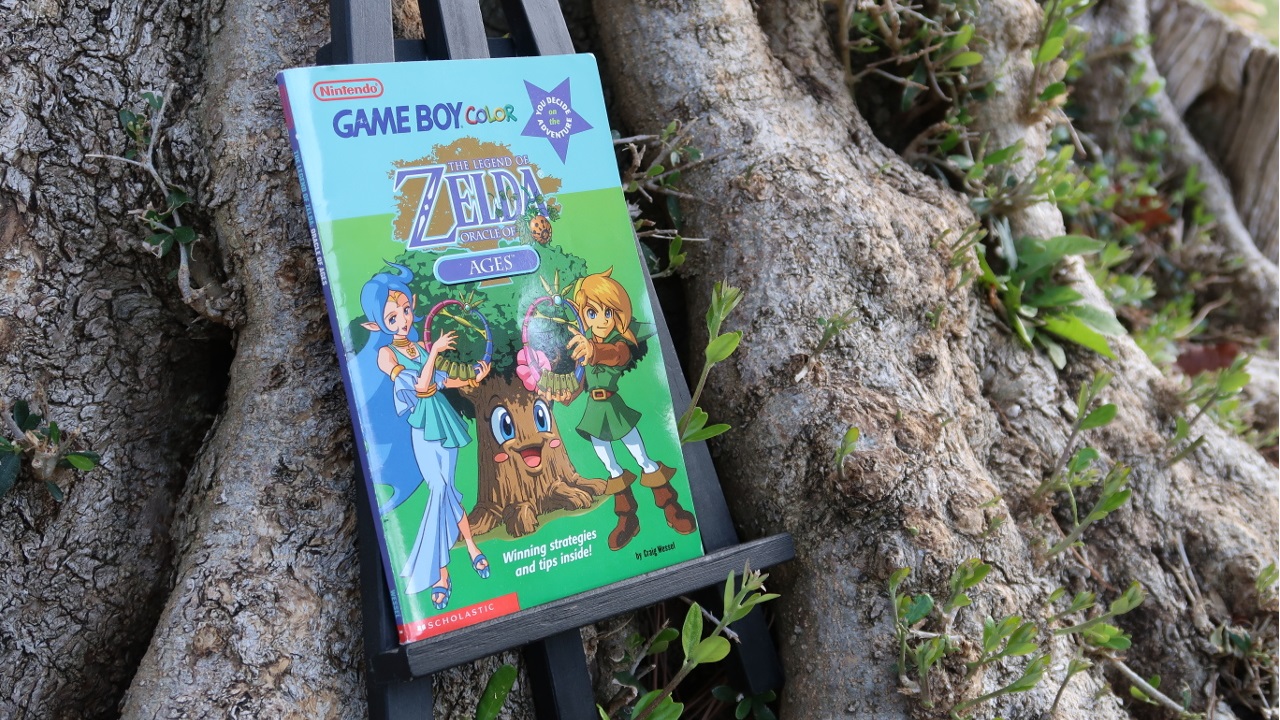

Judging the Book By Its Cover

First things first, I would be remiss if I did not mention that Scholastic’s Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons books are not technically Choose Your Own Adventure books.

The Choose Your Own Adventure series was created by Edward Packard and R. A. Montgomery in 1979. Originally published by Bantam Books, the series popularized the reader’s choice concept in children’s fiction and have since become shorthand for the concept itself.

However, the Choose Your Own Adventure brand is now a registered trademark strictly held by Montgomery’s Chooseco publishing company. As recently as 2019, Chooseco has remained notably litigious over the unlicensed use of the phrase, “Choose your own adventure,” in seemingly every medium, from advertisements, to video games, to television series. One could say Chooseco and Nintendo are a lot alike in that regard.

So, in order to be legally distinct from the Choose Your Own Adventure trademark, Scholastic’s Zelda books (and other similar Nintendo books) are branded You Decide on the Adventure. While the phrase does not roll off the tongue as easily as, “Choose your own adventure,” I completely understand the distinction.

The cover of the Oracle of Ages book, through some pleasant pieces of official art from the game, highlights three of the story’s main characters: Link, Nayru, and the Maku Tree. I would imagine that the cover was in part inspired by the game’s box, which also featured art of Link and Nayru and also made prominent use of the color blue. In contrast with Seasons‘ more action-oriented cover, Ages‘ cover appears much more relaxed and care-free, with the characters, all protagonists, smiling together. This positive approach definitely seems appropriate for the more cerebral and puzzle-focused Oracle game.

Interestingly, Scholastic made a rather bizarre change to the cover in later editions of the Oracle of Ages book. The 2003 edition features the male Maku Tree on the cover instead of the female Maku Tree, despite the fact that only the female Maku Tree appears in Oracle of Ages.

Now, I was willing to ignore the fact that the cover features two different instances of the Harp of Ages — only one of those things exists in the game — but I simply cannot let this particular Zelda lore faux pas go unreported. Get your stuff together, Scholastic! Didn’t you read the Zelda Dungeon Wiki?!

All joking aside, I can only assume that this alteration was a marketing decision. Perhaps the Seasons book was selling better than the Ages book at the time, and Scholastic — in a very North American Kirby box art kind of way — figured a cute, happy female tree was less marketable to young boys than a sly, winking male tree. Such logic ignores the fact that Seasons‘ cover is more appealingly active than Ages‘ and the fact that Seasons features more pages for the same price, but this is the only reasonable explanation I can come up with.

The book’s back cover features the story’s primary antagonist: the Sorceress of Shadows, Veran. Her artwork here does a great job demonstrating Veran’s strong visual design, as she could have very well served as an inspiration for future Zelda villains like Vaati. Personally, I don’t believe I would have connected as strongly with Veran (or Onox, antagonist of Oracle of Seasons) without this book, as her appearance on the Game Boy screen could not achieve as much visual flavor.

I may have also had a crush on Veran way back when.

Finally, the back-cover blurb gives readers an idea of the exciting adventure waiting to unfold within the book’s pages:

Nothing can stand in the way of Link’s quest to save the day — except maybe 400 years of time travel. Pack your bags and get ready for the trip of a lifetime.

It’s not exactly a detailed tease of things to come, but I can’t say I’m not excited!

And the blub concludes with a promise:

Remember, there’s more than just one ending. You get to decide what happens every time you read the book!

Speaking of promises, the book’s front cover also claims that there are “winning strategies and tips inside.” So, as we explore the many twists and turns of this You Decide on the Adventure adventure, we must be sure to take note of all the endings, and all the winning tips and strategies.

About the Author

But before we open this bad boy up, let’s first shine a spotlight on the author of both Oracle choose-your-own-adventure titles.

By 2001, author Craig Wessel had found success as a writer of strategy guides, having penned guides for big franchises like Quake, Unreal, Driver, and Duke Nukem. To this end, Wessel and his publishing company AHP Productions have worked with big game companies like id Software, Ion Storm, and Rogue Software, and he even wrote a series of video game Parent’s Guides around the turn of the millennium.

Wessel’s experience with strategy guides offers a unique perspective on his Nintendo-based adventure books, as, in promising those juicy “strategies and tips,” they strike an interesting balance between game walkthrough and adventure fiction. Much like the Nintendo Power Player’s Guide for Ocarina of Time, the Oracle books not only present Link’s adventure as any fantasy novel would — with third-person narration, dialogue, description, and character building — but they also walk readers through troublesome parts of the game, like certain dungeons and trading quests.

Keeping that in mind, it was a really interesting experience to read the Oracle of Ages book while also playing through the game.

Craig Wessel wrote four books in Scholastic’s Nintendo You Decide on the Adventure series, with Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons representing the Game Boy brand, and Super Mario Advance and Warioland 4 representing the Game Boy Advance. As someone who read all four titles in his youth, I would have certainly picked up more if other Nintendo properties had been adopted into the You Decide on the Adventure family. I’d imagine a Metroid or Pokémon adventure book would have been a big hit. But, according to Wessel, Scholastic never expressed interest in releasing more books for the series.

Beyond his work in the game industry, Craig Wessel has continued to stack up writing credits over the years as a ghostwriter, freelancer, contributor, technical writer, and author. His published work includes contributions to the Endlands horror anthology series, the suspense anthology collection Three On A Match, the espionage novel Darker Skies, and the San Diego Spy Games series. He also performs in a ZZ Top cover band called Trio Loco!

An Adventure for the Ages

Scholastic’s Oracle of Ages book, as most choose-your-own-adventure books do, begins by introducing readers to the adventure format and providing a few worthwhile instructions.

This special book is more than just one story about Link and his adventures in the land of Labrynna. You get to decide what happens every time you read the book!

Echoing the promises made on the cover, the instructions page excitedly claims that “there are several endings to this book” and that “you just might find some clues that will lead to secrets in” the Oracle of Ages game! Those are some bold claims indeed!

The instructions page also offers a brief primer on the Zelda series itself and Oracle of Ages‘ place in the grander story. The Legend of Zelda, the book explains, “has earned a reputation for delivering action-packed gameplay mixed with deep storylines and unforgettable characters.” Nothing but truth so far!

Link, the Hyrulian hero, must travel through time, exploring dungeons, collecting items, battling enemies, and completing quests in order to defeat the evil Veran, rescue Nayru, and return Labrynna to normal.

I really do appreciate that Scholastic and Wessel did what they could to make the story accessible to readers that had never played a Zelda game. All the information a reader would really need to get into the adventure is all present on the instructions page, and thus everything to follow can be read as a traditional fantasy story. In this way, these books could have realistically served as the first introduction to the Zelda series for some readers.

From there, the adventure begins! Following the early events of the game rather faithfully, the book first introduces the major players of the story. Link awakens “in a strange forest,” he quickly saves Impa from “several monsters,” the duo finds the singer Nayru and her guardian Ralph “deep in the forest,” and they all become “enchanted by [the] music.” The festivities are then interrupted by the evil sorceress Veran, who possesses Nayru and uses her magic to travel into the past.

“I am Veran, Sorceress of Shadows, and I have made the power of Nayru the Oracle of Ages my own! Now I can travel freely through time, and nothing can stop me from creating an age of shadows!”

Right off the bat, one can appreciate how closely the book follows the story beats of the game and how it does so in so few words. Oracle of Ages‘ entire opening is presented in just a page and a half, and Wessel’s writing, while understandably simple considering the book’s target audience, packs in a lot of detail. By the time Link heads off to Lynna City, readers will understand the stakes, know who the main characters are, and even recognize the relationships between those characters. The introduction makes plenty clear Ralph’s loyalty to Nayru and his initial distrust of Link.

After a short journey South for Link — and the turn of a few pages for the reader — our hero finds himself in Lynna City. It is here that the first choice is offered to the readers. Just like in the game, there are several buildings in the city that Link can enter, so readers can decide to explore one of the following locations: the shop, the ring shop, the mayor’s house, or a nearby home. Each choice will result in a minor encounter between Link and the occupant (or occupants) of the chosen location. Of the four buildings, the shop is the least worthwhile, as Link will just realize that he has no rupees to buy anything. But each of the other three locations at least offers something memorable for Link to do.

Visiting the mayor’s house will result in a silly little scene in which the mayor chatters on for an hour about the city and Link makes a re-election joke. Visiting the ring shop serves as fairly succinct introduction to the Oracle games’ ring mechanic; players will definitely know where to go to get the ring box in the game if they visit this location in the book. And visiting the nearby home will introduce readers to Bipin and Blossom.

One of the more interesting side quests in the Oracle games involves Link visiting the young couple Bipin and Blossom and influencing the development of their son from infancy to adulthood. At the onset of either game, Link can visit the couple and help name the child; the player gets to choose the name. Both Oracle books present this initial meeting, with the Link of the books choosing to name the baby “Bipsom,” a portmanteau of his parents’ names.

Put on the spot, Link thought for a moment and said, “Why don’t you name him Bipsom, after both of you?”

The parent’s smiled, “That’s a wonderful idea, Link! Bipsom he shall be!”

While Bipsom is considered the canon name for this character, players can’t actually name him that due to the name being limited to five characters in the games. So, in my most recent playthrough, I had to go with something a little different.

No matter which location they choose to visit in Lynna City, the reader will always be pointed to the Maku Tree next, which, unfortunately, illustrates the book’s deficiencies as a choose-your-own-adventure title. Ultimately, other than a few obvious life-or-death situations, the story of Oracle of Ages will always proceed the same way no matter what choices the reader makes. Despite even minor diversions like the ones we see here in Lynna City, the destinations of Link’s quest always remain the same.

In this regard, I can’t help but think of complaints leveled at games like Heavy Rain or Telltale adventure titles, games that simply offer the illusion of choice while preserving roughly the same outcome for every playthrough. I understand that these Oracle books were targeted to children, but by promising “more than one ending,” they are setting up some readers to be disappointed, especially if those readers are eager to replay the adventure multiple times and see what they may have missed. At the very least, a few more silly endings or branching story paths that last longer than one page would have made a big difference.

In this regard, I can’t help but think of complaints leveled at games like Heavy Rain or Telltale adventure titles, games that simply offer the illusion of choice while preserving roughly the same outcome for every playthrough. I understand that these Oracle books were targeted to children, but by promising “more than one ending,” they are setting up some readers to be disappointed, especially if those readers are eager to replay the adventure multiple times and see what they may have missed. At the very least, a few more silly endings or branching story paths that last longer than one page would have made a big difference.

Speaking of alternate endings, let’s examine the first “bad ending” readers can find in Oracle of Ages.

After speaking to the Maku Tree, travelling back through time, and completing the first dungeon — the book presents these events rather faithfully — Link’s next objective is to enter the second dungeon, the Wing Dungeon. However, as those who have played through Oracle of Ages will know, the entrance to the dungeon has collapsed in on itself in the present. So, our hero must retrieve the fabled Harp of Ages from Nayru’s house and travel back in time, where the dungeon’s entrance is still in tact.

In the Oracle of Ages book, readers are presented an important choice once Link gets his hands on the harp.

Once he had the Harp, he discovered that it would allow him to open a Time Portal to the past.

What should Link do next?

Return to the crumbled cave.

Turn to page 18Use the Harp of Ages.

Turn to page 50

The correct choice is to obviously use the Harp of Ages to go back in time, and then journey to the past version of the Wing Dungeon. But, if a reader so chooses to return to the crumbled cave, they’re in for a surprise.

Link decided to return to the crumbled cave, so he set out across the forest again. Things were going fine when suddenly, he came to a clearing that was swarming with Octoroks! Before Link could draw his sword, the Octoroks had surrounded him and knocked him to the ground.

As he lost consciousness, Link could only think about poor Nayru, and his failure to save her.

The End

You’ve reached one of the worst possible endings of this story! Care to try again?

I think we’ve all been there before.

This unfortunate turn of events is very similar to the other failed endings in Oracle of Ages, of which there are four. And, for the most part, the poor decisions that result in these endings are easily recognizable as poor decisions. There are no ambiguities or shades of grey in these choices, so I’d imagine the only readers that would fall victim to these bad endings are very small children or hopelessly thorough games writers.

Oracle of Ages can end in one of five ways:

- Link will, just like in the actual game, vanquish Veran, rescue Nayru, and save Labrynna on page 42.

- Link will die unceremoniously to a pack of Octoroks on page 18.

- Link will die unceremoniously to a swarm of Moldorms on page 58.

- Link will misjudge a jump over a bottomless pit and fall to his death on page 22.

- Link will be caught sneaking past a group of palace guards and be locked away in a prison cell on page 44.

Of this zesty platter of alternate endings, I think the one on page 44 is my favorite. Link’s capture and imprisonment is described with such a depressing and bitter tone; it almost feels out of place in an otherwise whimsical children’s story.

They locked him in an old, moldy cell in the dungeon. “That should keep you until the Queen is ready to deal with you.” Link couldn’t believe how foolish he had been.

“Now Veran will rule the land, and Nayru will be her prisoner forever.” Link hung his head and waited for Veran to destroy him. From the looks of this cell, he thought he might be waiting a long, long time.

And now we know how a Hero’s Shade is born.

Up to the completion of the game’s second dungeon, the Oracle of Ages book was, as mentioned, surprisingly faithful to its source material. But once Link emerges from the Wing Dungeon, Scholastic’s story starts to skip over a few key sequences from the video game. Certain omissions were to be expected, of course, as the book only has so many pages to adapt a game that can take anywhere from five to 20 hours to complete. But it’s still rather interesting to examine what events the author / publisher chose to cut and how they chose to execute those cuts.

Some story removals were more elegant than others. For example, the various events between the Moonlit Grotto and Jabu-Jabu’s Belly are waved away with a few brief sentences.

…Link’s search took him all over the land. As he travelled, he used the Harp of Ages to go back and forth in time to find what he needed. The Maku Tree continued to provide support and help to Link as he travelled.

The inclusion of these lines at the very least smooths over such a big jump in continuity and maintains a good pace for the story. From a writing perspective, the emotional core of the narrative lies with Veran and Nayru; if we had followed Link through every single dungeon and sidequest from the game, that emotional core would have been diminished and the pace would have suffered.

But I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t disappointed that some of the more memorable scenes from Oracle of Ages were neglected by the book. The entire Crescent Island trading sequence, the Symmetry City / Symmetry Village quest, and the Gorons of Rolling Ridge are all absent. And as much as I absolutely loath Goron Dancing in the game, I would have loved to read about our hero struggling to match the Goron dancers’ steps.

But let’s talk about some instances where the book is its most clunky in skipping over the game’s content, shall we? As I mentioned, Crescent Island is not well represented in the Ages book. In fact, most of the lead-up to the Moonlit Grotto is completely brushed over. Instead of Link undergoing a convoluted quest to find Flippers, rope, and a raft, our hero instead simply meets the animal companion Moosh, who helps him reach the Grotto… somehow.

Link discovered that if he rode on Moosh’s back, he could easily cross pits and other obstacles. This made it much easier for him to reach the Moonlit Grotto.

And in the very next sentence, Link is exploring the first room of the Moonlit Grotto. There is no mention of Crescent Island, no mention of crossing an ocean, and no mention of being shipwrecked.

While I would have simply forgiven this plot development as an awkward way of moving the action along, issues continue to compound themselves after Link leaves the Moonlit Grotto.

Link left the dungeon, but he had a problem. There was no way to cross the water and return to Lynna City! Link walked to the coastline and began looking for a way across. He came across some Tokay arguing over a water-going Dodongo they’d found near the shore.

What water?! What coastline?! What’s a Tokay?!

Essentially, the story of the book removes the establishing details of Link’s quest to the Moonlit Grotto — the ocean, the shipwreck, the Tokay tribe — but fails to compensate for that removal once Link leaves the dungeon. Events proceed exactly as they do in the game: Link saves Dimitri the Dodongo, and the duo crosses the ocean to return to Lynna City.

At this particular moment, I can’t help but suspect that the publisher removed pages or story sequences from the book after the author had submitted the final draft. Perhaps Craig Wessel had included Link’s quest for the raft and the Tokay trading sequence initially, but Scholastic deemed it necessary to trim the story down even more. We may never know the exact circumstances, unfortunately.

Similar moments occur all throughout the Oracle of Ages book, as characters or objects are not properly introduced but readers are expected to know about them anyway. For example, at one point, Link pulls out the Seed Shooter to solve a puzzle even though readers never learn of him acquiring that item beforehand. I had to flip back through the pages during my read-through just to make sure I didn’t miss something.

All of these strange story cuts add up, and I wouldn’t be surprised if quite a few children found themselves confused when reading through the book back in the day. And, in comparing Oracle of Ages‘ 61 pages to Oracle of Seasons‘ 96 pages, such cuts seem wholly unnecessary in the first place.

And here’s one last interesting omission from Oracle of Ages‘ original story. Just as the Gorons of Rolling Ridge are absent from the book, so are the Moblins of Great Moblin’s Keep. Now, I wouldn’t normally see this as a very big loss, but for some odd reason, the book still features artwork of Great Moblin among its tipped-in pages.

To clarify, both Oracle books, in addition to the standard pages of text, include several tipped-in pages inserted at the center. These pages feature character descriptions and some really nice pieces of official artwork from the game. For example, Oracle of Ages‘ tipped-in pages feature artwork of Link, Nayru, Veran, Bipin & Blossom, Vasu the jeweler, and Maple the witch, all characters that appear during the book’s story.

However, the last tipped-in page features Great Moblin, boss of Great Moblin’s Keep in Oracle of Ages.

Great Moblin

Big, bad, ugly, and just plain mean. The Moblin King is out to stop Link.

Great Moblin’s inclusion among the tipped-in pages, and the limited number of pages in the Ages book overall, leads me to believe that the Great Moblin — and perhaps also Rolling Ridge and the Goron quest — was originally meant to be included in the book. But, for some unknown reason, this character — and perhaps those story sequences — was left on the cutting room floor. It’s really too bad; I would have loved to see a failed ending where Link blew himself up with a giant bomb.

As I read through Oracle of Ages earlier this month, I was surprised by how many of the game’s dungeons were actually represented in the book. Of the game’s nine main dungeons, the book describes six: Spirit’s Grave, Wing Dungeon, Moonlit Grotto, Jabu-Jabu’s Belly, Ancient Tomb, and Black Tower. The book even includes all the boss and mini-boss fights in these dungeons!

I also found it interesting that Oracle of Ages allows readers to tackle Jabu-Jabu’s Belly and the Ancient Tomb in any order they want, one of the best examples of the book making the most of its choose-your-own-adventure format. Players of the video game are not be allowed such freedom, but this non-linearity does continue the tradition of some past Zelda games which let players approach certain dungeons out of order — like A Link to the Past and Ocarina of Time — and predict the non-linear Zelda games of the future — like A Link Between Worlds and Breath of the Wild.

Craig Wessel also deserves a lot of credit for describing some of these dungeons and their mechanics with just words on a page. Painting a word picture of such crudely depicted rooms on a Game Boy screen seems like a pretty difficult task indeed!

Seriously, how would you describe this room in Moonlit Grotto?

Living up to the promise of “winning strategies and tips,” every dungeon scene in the book includes at least one helpful hint or puzzle solution. The book may reveal the location of a dungeon map or key, it may demonstrate the primary goal of a given dungeon, or it may explain how to take down a particular enemy. In fact, reading through the dungeon sections of the book helped me defeat the Head Thwomp and Shadow Hag bosses when I played through those sections in the game!

Living up to the promise of “winning strategies and tips,” every dungeon scene in the book includes at least one helpful hint or puzzle solution. The book may reveal the location of a dungeon map or key, it may demonstrate the primary goal of a given dungeon, or it may explain how to take down a particular enemy. In fact, reading through the dungeon sections of the book helped me defeat the Head Thwomp and Shadow Hag bosses when I played through those sections in the game!

Once Link has collected all eight Essences of Time, he proceeds to the Black Tower for his final confrontation with Veran. He scales the structure, he saves Ralph (who the book completely forgets about midway through), and he banishes Veran’s spirit from Queen Ambi’s body. The final two pages of the book describe the epic battle between our hero and the dark sorceress, offering readers a few more winning tips and strategies before the story concludes.

And, living up to his role of the hero of legend, Link vanquishes the Sorceress of Shadows and saves the kingdom of Labrynna!

With one final blow, Veran disintegrated. The Black Tower began to collapse. Link found himself transported to the Maku Tree before the tower could destroy him.

The Maku Tree and Nayru thanked him for his help, and they put up a statue in his honor. Link was a hero once again, and the land was safe from Veran’s evil schemes.

Nayru launched into a song of celebration. The people of Lynna City gathered around, celebrating their freedom from Veran.

The End

This ending is very faithful to the Oracle of Ages game, Link statue and all! And while readers will receive no indication that a separate adventure exists in Oracle of Seasons or that both games linked together begets even more adventure, I’d imagine most readers will step away from their victory satisfied. They have overcome evil and saved a kingdom!

However, I can’t help but feel a way about the book’s parting words to the reader.

Be sure to read this book again, and make different choices!

Readers are encouraged to read the story again, which I fully support if they enjoyed the adventure and want to re-live it again. But I certainly would not recommend any readers make different choices throughout the journey, unless they want to visit one or two different places in town or they want read about Link failing in farcical ways.

Conclusion

This re-examination of the Oracle of Ages book has shown just how shallow it is as a choose-your-own-adventure experience. Most of the choices a reader can make are superficial, and there is only one worthwhile ending. A few additional endings or branching paths in the story — something outside of the good ending / bad ending binary — would have gone a long way to expand upon the adventure format and encourage readers to run through the story again.

I do however recognize the value of the book as a supplemental resource for players of Oracle of Ages, especially as a primer for the game or as a unique type of strategy guide. It’s no Zelda Dungeon guide or anything, but the book has its fair share of tips and tricks. The aforementioned boss tutorials and the Noble Sword trading quest walkthrough on page 30 seemed extremely valuable to me!

The adventure format and flavor text of Oracle of Ages may not always live up to their potential, especially as certain gameplay segments are cut out or overlooked, but the book still contains plenty of worthwhile tips and information for players seeking a primer for the true adventure on their Game Boy system. As mentioned, reading the book to completion before picking up the game could help new players find a firmer grasp on the story, characters, and world, and it could offer them some crucial directions during the early parts of the game. And as Link’s journey continues on, readers may find helpful resources all throughout the book.

Looking back 20 years after the release of Oracle of Ages & Seasons, I remain thankful that this book helped me fall in love with The Legend of Zelda and with fantasy stories in general. My hope is that my story is not a unique one, and that many Zelda fans can look back fondly at this flawed but charming adventure book. At the very least, both Oracle books remain unique oddities of a special time in Zelda history.

Be sure to check out our retrospective of the Oracle of Seasons choose-your-own-adventure book right here!

Did you read the Oracle of Ages book as kid? Do you have any cool memories? Did this book introduce you to the Zelda series? Let us know in the comments below!

Rod Lloyd is the managing editor at Zelda Dungeon, primarily overseeing the news and feature content of the site. The Zelda Dungeon Caption Contest and Zelda Dungeon themed weeks are both Rod’s babies. You can find Rod on Twitter right here.

Rod Lloyd is the Editor-In-Chief at Zelda Dungeon, overseeing the news and feature content for the site. Rod is considered the veteran of the writing team, having started writing for Zelda Informer in 2014 as a Junior Editor. After ZD and ZI officially merged in 2017, he stepped into the Managing Editor role and has helped steer the ship ever since. He stepped up to lead the writing team as Editor-In-Chief in 2023.

You can reach Rod at: rod.lloyd@zeldadungeon.net