How Zelda Has Dropped Out of Mainstream Gaming Conversation

Posted on July 05 2013 by Legacy Staff

The last article I wrote began with a call to arms for Nintendo. They were being left behind in the new culture of gaming, I said, because of their reliance on gameplay to the detriment of their story. I pitched a grand vision of a single Link’s tale concluding in the upcoming game A Link Between Worlds. I talked about how they should allow that story to connect with the gameplay by allowing players to traverse a Hyrule changed since the events of A Link to the Past, and allow players to experience the strangeness of being in a familiar but changed land just as Link does in the game’s story.

The last article I wrote began with a call to arms for Nintendo. They were being left behind in the new culture of gaming, I said, because of their reliance on gameplay to the detriment of their story. I pitched a grand vision of a single Link’s tale concluding in the upcoming game A Link Between Worlds. I talked about how they should allow that story to connect with the gameplay by allowing players to traverse a Hyrule changed since the events of A Link to the Past, and allow players to experience the strangeness of being in a familiar but changed land just as Link does in the game’s story.

Further information has since come out that has made that possibly less likely (though still possible, and I continue to hope!), as it was confirmed that A Link Between Worlds is not a direct sequel. Though it was received with muttering and minimal discussion, I fear that this news is yet another symptom of a sickness that has been plaguing the Zelda franchise for quite some time now. This sickness is the reason for the franchise dropping out of mainstream gaming conversation. This sickness, I believe, is responsible for the disappointing sales of Skyward Sword.

Today, we’re going to talk about just what this sickness is, why it’s affecting the franchise, and how the franchise can cure itself of the affliction.

Growing Pains: Video Gaming’s Awkward Adolescence

I’ve said it many times, and others have said it as well: in terms of its growth as an artistic medium, video gaming is very much in its adolescence. Given how far we’ve come from the early days of games like Pong and even the original The Legend of Zelda title, it may be tempting to leap ahead and say that gaming has fully matured as an art form. But that’s not entirely accurate, as we’re still in an awkward adolescence, replete with growing pains and strange contradictions. The Legend of Zelda fits quite cleanly into this adolescent period, being a perfect example of one such growing pain. To really dig into why this is, we’re going to have to look at the basic four ways that people engage with works of art, as outlined by the incomparable internet critic Film Crit Hulk (if you decide to seek him out, be wary that Hulk can get very adult and use some harsh language in his criticism).

A better term might be four different levels that people engage with art, as everybody starts at the first level, and has to work their way up to the other three. Before I describe them, however, I want to make it abundantly clear that there is nothing wrong with any of the four levels. The fourth level may be the “highest”, but that is not because it is inherently “better” than levels one through three; it’s on top simply because one must pass through the first three levels in order to engage with a work of art on the fourth level. It’s a vertical progression, from level one up to level four. One more time: no level is inherently better than the others. Alright, ready? Here we go.

A better term might be four different levels that people engage with art, as everybody starts at the first level, and has to work their way up to the other three. Before I describe them, however, I want to make it abundantly clear that there is nothing wrong with any of the four levels. The fourth level may be the “highest”, but that is not because it is inherently “better” than levels one through three; it’s on top simply because one must pass through the first three levels in order to engage with a work of art on the fourth level. It’s a vertical progression, from level one up to level four. One more time: no level is inherently better than the others. Alright, ready? Here we go.

The first level is occupied by people who engage with art with a high degree of “transference”. What this means is that people engaging on the first level will experience a piece of art – for example, a movie – and will be able to more or less directly place themselves into the situation the movie is displaying. There’s a strong emotional connection with everything in the work, and it results in very positive emotional experiences for the person. The characters defeat the villain, and the person engaging on this first level is excited and joyful. But because of this strong emotional connection, people on this first level will almost always shy away from works of art that create negative emotions. They will dislike movies in which the main character dies, because it will make them sad. They won’t care much for movies built on shock or suspense because these are uncomfortable emotions.

But eventually people can move beyond this level and up to the second level. On the second level, people have acquired a necessary skill called “narrative distance”. People engaging with works of art on this level can detach themselves from the work of art in question, and will thus be more apt to enjoy works that deal with negative emotions such as sadness and fear. Because they aren’t directly placing themselves in the narrative of the film, dealing with the negative emotions is easier. But the flipside to this is that people operating on this second level seek to regain the sorts of experiences they had on the first level. The downside to “narrative distance” is that the emotional reactions are not quite as strong as they once were, and people operating on this second level still wish to reclaim those emotions. As a result, they’ll often chase the same sorts of experiences they did on the first level.

Again, as we discussed earlier, there is nothing inherently wrong with any of these approaches. But what separates these first two levels from the next two levels is part of something called the “tangible details theory”. The theory is a larger one that addresses the nature of criticism as a whole, but the pertinent point is this: there are certain “tangible details” in art that nearly every person experiencing that art will be able to perceive: in films, these are things like acting, the soundtrack, the basic narrative, and so on. But there are other details, known as intangible details, that not everybody will perceive, and that often require more active reflection to pick up upon. These are often the greater points that a work of art is trying to make. It’s often not quite as simple as something like the theme, but it’s along those lines: it’s a greater argument being made by the work of art.

The reason that these first two levels are not considered fully developed (as both of these next two levels are) is that they limit themselves to the tangible details. The development of narrative distance is necessary in order to begin perceiving the intangible details, but because both groups only seek the sorts of visceral emotional reactions that being very close to the work of art will bring, they’re actively ignoring the intangible details beneath the surface. This is perfectly fine and a valid way of experiencing art – but it isn’t fully appreciating it, it isn’t getting everything that one can get out of engaging with art.

The reason that these first two levels are not considered fully developed (as both of these next two levels are) is that they limit themselves to the tangible details. The development of narrative distance is necessary in order to begin perceiving the intangible details, but because both groups only seek the sorts of visceral emotional reactions that being very close to the work of art will bring, they’re actively ignoring the intangible details beneath the surface. This is perfectly fine and a valid way of experiencing art – but it isn’t fully appreciating it, it isn’t getting everything that one can get out of engaging with art.

The third level is marked by an awareness of those intangible details and an ability to place the emotional experience into a greater context. People engaging with art on this level will be able to, through the work of art, open conversations about things much larger than the work of art in question. They will see a movie about a difficult break-up for two people, and then take the emotional experience they have from that movie and use it in a conversation about the nature of human relationships. When you see people analyzing works of art in depth, they’re almost always operating on this level. This level is one that we can consider fully developed, one that does not restrict itself to tangible details but instead digs into the intangible details to open dialogues about subjects larger than the work of art.

Now, the third level is considered fully developed: so how can there be a fourth level? The fourth level is very difficult to reach, because it necessitates an understanding of the craft of making art. A person operating at the fourth level will engage with a work of art just as somebody on the third level would, but as they do so they can see the many ways that the work of art was created in order to deliver the experience that they are experiencing. If they are watching a film about a break-up, they’ll observe the camera shots and the lighting of scenes and note how they are all done in such a way as to make the observer feel a greater sense of sadness and loss. It’s difficult to reach this level because not everybody has a chance to create works of art often enough to reach this level of proficiency; but those who do, like the people on the third level, are able to probe into a work of art and expose greater dialogues.

These are the four basic ways that we engage with art. Reading through these, I would wager that you can probably trace your own progression through them and pinpoint where you currently reside. Keep in mind (I cannot stress this enough), that no matter where you are, you are consuming art in the way you want to and there is absolutely nothing wrong with being at level one or two as opposed to three or four. But these four ways are very recognizable, and I am confident that most of you can identify with each of the mindsets at some point in your past. So, how does this relate to gaming?

When gaming started, nobody had any experience with the medium – it was a brand new thing, and there were no close analogues. So everybody who picked up a game during the first few years was operating on the first level, since we all start there and move up the ladder by consuming more art. Gradually and gradually the collective gaming audience began to move up the ladder. Many people reached level two, and a small number reached level three. Then the generations changed, and former game players became game developers, and we began to get games that were more geared towards people at the second level: games that dared to have a bit more narrative hardship to nurture that narrative distance. Games that were less about the immediate elation and fun of gameplay and more about telling stories. Then the kids who grew up with these games began to make games… which brings us to now.

When gaming started, nobody had any experience with the medium – it was a brand new thing, and there were no close analogues. So everybody who picked up a game during the first few years was operating on the first level, since we all start there and move up the ladder by consuming more art. Gradually and gradually the collective gaming audience began to move up the ladder. Many people reached level two, and a small number reached level three. Then the generations changed, and former game players became game developers, and we began to get games that were more geared towards people at the second level: games that dared to have a bit more narrative hardship to nurture that narrative distance. Games that were less about the immediate elation and fun of gameplay and more about telling stories. Then the kids who grew up with these games began to make games… which brings us to now.

We are in gaming’s adolescence because the gaming community at large is split between levels two and three. In fact I’d even argue a lot of gamers occupy a strange nether region between levels two and three. There is this elevation of retro gaming and nostalgia that exists, and yet there are wide conversations being started by games like BioShock Infinite and The Last of Us about issues much larger than both the games themselves and the gaming community itself. We are torn between the pure elation of the bottom levels and the more cerebral artistic expression and discussion of the top levels.

Where does The Legend of Zelda sit? For all its 25 years, The Legend of Zelda has sat quite firmly in the bottom two levels. Around the time of Ocarina of Time, I argue, it moved up to the second level, where it has remained ever since. This is where the sickness of indulgence enters into the fray.

Indulgence: The Legend of Zelda’s Inability To Keep Up

From day one, The Legend of Zelda’s greatest achievement has been its gameplay. There are few games that manage to be as simply fun and exciting as this franchise has historically been. The gameplay has always been well-conceived and executed with great precision and finesse. It’s rarely made missteps, and never major ones. It’s a major reason why, with the exception of the journey to 3D in Ocarina of Time, the gameplay of the series has been iterative at best: the core has remained virtually the exact same over 25 years.

From day one, The Legend of Zelda’s greatest achievement has been its gameplay. There are few games that manage to be as simply fun and exciting as this franchise has historically been. The gameplay has always been well-conceived and executed with great precision and finesse. It’s rarely made missteps, and never major ones. It’s a major reason why, with the exception of the journey to 3D in Ocarina of Time, the gameplay of the series has been iterative at best: the core has remained virtually the exact same over 25 years.

But gameplay is a tangible element, and the elation and joy of gameplay is very much a first level experience.

Yet again, there’s nothing wrong with that. As the franchise began to become a bit more story-driven around the time of Ocarina of Time, it graduated to the second level and acquired a bit of confidence in its players’ ability of narrative distance. But there it has remained, and the issue with this is that instead of moving up to the third level, it has simply indulged the players’ desire for that elation and joy through the tangible element of gameplay. There’s that term: indulgence.

Indulgence is a perfectly valid thing. Everybody indulges themselves with some absurdly sweet food at some point, or with a purchase they probably shouldn’t have made. Indulging is healthy. But the constant pursuit of an experience that was positive, to diminishing results, is the ugly side of indulgence. This is why the gaming community at large has begun to turn away from the Zelda franchise. You regularly hear stories of people no longer finding new entries in the series exciting, about finding them rote and samey. This is the stomach cramp that comes after indulging on too many chocolate bars. You get sick of them because you’ve indulged too much.

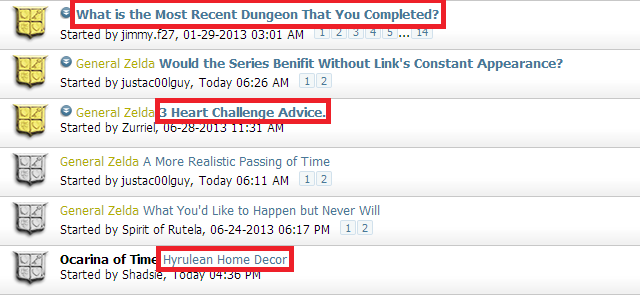

Meanwhile, the people turning away from the frequently indulgent games in the Zelda series are turning instead to games that are conducive to third level engagement: games that open up larger conversations. You will almost never see discussions about Zelda games that talk about the nature of violence or the morality of survival, and yet these big topics are the very sort of thing that recent games such as BioShock Infinite and The Last of Us have been sparking all across the gaming community. These games have opened up dialogues, because a large part of the gaming community has moved onto the third level of engagement. They’re digging past the tangible elements of basic gameplay and basic plot and boring into the intangible elements of the interplay between the gameplay and the plot (and throwing around terms like “ludonarrative dissonance”, something we will discuss in a moment). These are conversations that the broader gaming community is having: what conversations is the Zelda fanbase having?

Now let’s be clear: I’m not disparaging these conversations. I engage in them quite frequently, and find them very entertaining. The reason I bring these up is to illustrate a disconnect. The gaming community at large is touching topics well beyond the scope of gaming: they’re talking about violence, morality, survival, the very nature of human relationships (games like The Walking Dead and Journey have made great strides in sparking these kinds of discussions). Meanwhile, we’re talking about what we most recently did in a game, how to complete a game in the series with certain restrictions on ourselves, and the nature of home décor in the series. There is a fundamental difference between the engagement of art among the gaming community at large and among the Zelda fanbase. And that’s absolutely, totally fine. But it’s a symptom of this sickness of indulgence that is resulting in the Zelda franchise dwindling in relevance and popularity, something that – if left unchecked – could result in an end to the franchise.

I don’t mean to be all doom and gloom about this – even though my use of the word “sickness” may imply that. The reason I use the term sickness to describe the series’ pattern of indulgence – apart from the term completing my wonderful too-many-chocolate-bars metaphor – is that I think the pattern contributes to a gradual stagnation of not only the gaming industry (meaning the economic aspects), but also of the art form and the progression of gamers as consumers of art. If we’re stuck in a constant loop of being indulged by the newest Zelda game, we’re not going to ever evolve out of this second level of artistic engagement. And while it’s okay to stay at the second level forever, it will preclude us from having the sorts of discussions that the rest of the gaming community is having. Art has the unique power to reveal universal truths and ideas through emotional experiences; if we’re stuck in a loop of indulgence, we’re missing out on that.

So I use the term sick to describe that. These aren’t discussions that everybody has to have or even that everybody wants to have; but they are discussions that we should be able to have if we so desire. This sickness is holding us back.

So We’re Sick: How Do We Fix It?

I’m so glad you asked, section header!

I’m so glad you asked, section header!

I’m going to make this rather plain: this is a very easy problem to fix. I’m going to make the solution even plainer: toss out the philosophy of “gameplay first”.

Several Zelda developers have stated that their game design philosophy involves starting the production of a game with a core gameplay element, and then developing the game from that element outward; most recently, series producer Eiji Aonuma said this in relation to Skyward Sword’s development and the lack of emphasis on the timeline as a result of their “story second” approach to game development.

Our discussion so far should illustrate the problem with this philosophy: by developing from a gameplay element, they are basing the entire game around a tangible element. This will obfuscate the incorporation of intangible elements due to the focus of the game being placed front and center. I’m a filmmaker myself, and one of the biggest lessons I have learned is that when writing a film, it is always best to start with an emotional idea, some argument that you want your eventual film to make, and then allow the story and style of your film to grow from that idea. That is starting with an intangible element and developing outward, tailoring the tangible elements to suit the intangible element. Aonuma’s stated development philosophy is starting with a tangible element and then developing outward. This is a problem for several reasons.

If we can briefly jump back to the conversations the gaming community is having regarding recent releases BioShock Infinite and The Last of Us, we can see quite clearly where the bulk of the conversation comes from: the intersect between gameplay and story, the tangible elements that lead to the intangible elements. In the case of BioShock Infinite, much of the discussion about violence has started as a result of the “ludonarrative dissonance” in the game. “Ludonarrative dissonance” is a big fancy term referring to a tonal disconnect between the gameplay and the story of the game. In the case of BioShock Infinite, it refers to the hyperviolent gameplay clashing with the story, setting, and characters of the game, which is at its core a story about a surrogate father/daughter relationship. Elizabeth is directly designed with reference to classic Disney princesses, so to have her story with main character Booker be interspersed with gameplay segments of intense violence is the core of that ludonarrative dissonance. That interplay between the gameplay and the story opened up dialogues all across the gaming community, with major editorials on nearly every major gaming news outlet.

Similarly, The Last of Us has been praised for having gameplay that enhances the story and vice versa. Being a harrowing game about survival, the story is dark and brutal – just as the gameplay is. Player character Joel is a very brutal and violent man, both in physical confrontations and in emotional ones. The story and the gameplay reinforce each other, and raise questions about the nature of survival. These questions have been discussed in about equal measure as the BioShock issue of violence, with many editorials popping up on gaming websites in the weeks since the game’s release.

The point to take from this is that the games that generate discussion almost always do so as a function of the interplay between story and gameplay. Both story and gameplay are tangible elements, and they work in the service of the intangible elements at play in these games, and they call attention to them and give rise to much public discussion of these elements. The issue with the Zelda franchise’s stated design philosophy is that developing a game around a gameplay concept will inevitably result in a game whose story works in the service of the gameplay – one tangible element working for another – rather than a game whose story works with the gameplay in order to discuss larger ideas.

Note that it also isn’t enough to simply reverse the philosophy and develop story first; it is absolutely critical that they are developed in tandem so that they have a greater interplay. In fact, there’s an example of a game where the developers took the “story first” approach: Twilight Princess. While it sold better than Skyward Sword, it has taken on the ire of a great number of Zelda fans, as well as having also escaped greater discussion in wider gaming coverage. Despite the reversal of design philosophy, the game was no more adept at fostering discussion.

If we want Zelda to be relevant and discussed on the level that it once was, it is no longer enough to be a gameplay leader. The gaming community at large is operating on that third level of artistic engagement. If we want Zelda to be talked about, it needs to change its design philosophy to accommodate the discussion of intangible elements.

One More Thing

So that was a lot of words to get to a very simple point! That’s what I do, though. I love the Zelda series with all my heart – indulgent or otherwise. This series is responsible in large part for who I am today, and is something that I will forever cherish. It is for that reason, however, that I desperately want it to change in order to survive.

So that was a lot of words to get to a very simple point! That’s what I do, though. I love the Zelda series with all my heart – indulgent or otherwise. This series is responsible in large part for who I am today, and is something that I will forever cherish. It is for that reason, however, that I desperately want it to change in order to survive.

I’ve been operating on the third level of artistic engagement for some time (I like to believe, at least). I greatly enjoy teasing at the deeper ideas hidden within games and discussing them. That enjoyment, in fact, has been the driving factor behind nearly every article I’ve written here at Zelda Dungeon. I apply literary theory to these games because I want to show people that there is tremendous depth to be found here if we only look.

But even as I do so, the stated philosophies and goals of the developers seem to undercut my efforts at every term. Their apparent disregard for story and elevation of gameplay above all seems to send the clear message, to me at least, that they are concerned more with indulging their audience than engaging them. That they want their audience to have fun with their games rather than think about them. And that’s absolutely fine.

But what’s wrong with doing both at once?

The best games are fun and thought-provoking in equal measure. The best games can be enjoyed on any of the four levels of artistic engagement. But as I grow older and play more and more Zelda games, I am less and less able to engage with them as I would like to.

But ultimately, I want to close this (very long) article with a question to you, constant readers and Zelda fans. My inclinations are clear – I want the series to embrace these intangible elements, and develop their gameplay and story together in a way that strengthens the whole, rather than story working in the service of gameplay.

But what do you want? Do you want to see the series continue to be an indulgent one, delivering exciting and fun gameplay above all else? Do you, like me, want the series to veer in the direction of thought-provoking discussions of big topics?

Should the series change, or should the series remain as it always has – an indulgent, but effortlessly enjoyable, pillar of gaming history?