- Joined

- Apr 10, 2019

"Vah Medoh" by ArtsyShionai

Wherever Teba looked, he saw chaos. Plumes of smoke rose from recently quenched fires that marred the wooden platforms and staircases spiraling around the single, narrow mountain spire on which Rito Village was built. Feathers drifted lazily on the heated air, belying the deadly swiftness with which disaster had struck the bird-like creatures’ ancestral home. Those falling plumes caused Teba’s already simmering temper to boil over into a towering rage, one that had only briefly subsided as he took time to stop. To breathe. To make sure he was alive.

Those feathers belonged to his people. The snow-white plumage that enveloped Teba’s head and neck rose, like hackles on the winter wolves that prowled Dronoc’s Pass to the north. He looked skyward, his rage at war with the tears brimming in his golden eyes. His sight was second to none among the Rito. Those twin golden orbs had spotted Hyrule bass when all but he gave up Lake Totori for empty. In such lean times, the Rito’s most respected warrior had kept his people from starving. Now, all he wanted to do was keep them from dying.

Teba’s eyes did not need to focus on something as small as fish on this day. They found their target with pathetic ease. It loomed over the village, its shadow blotting out the sun and drowning his people’s home in unnatural midday darkness. The silhouetted shape in the sky looked like an enormous bird, but Teba knew it was not.

His breath rattled, emotions washing over him like the “lava” Kaneli had described when he was a chick: red water that flowed from the top of Death Mountain far to the east, the red water that could kill all but the Gorons who lived there. Kaneli said that, during the time of the Great Flood, this same “lava” had once formed the stone pillar upon which his own village flourished.

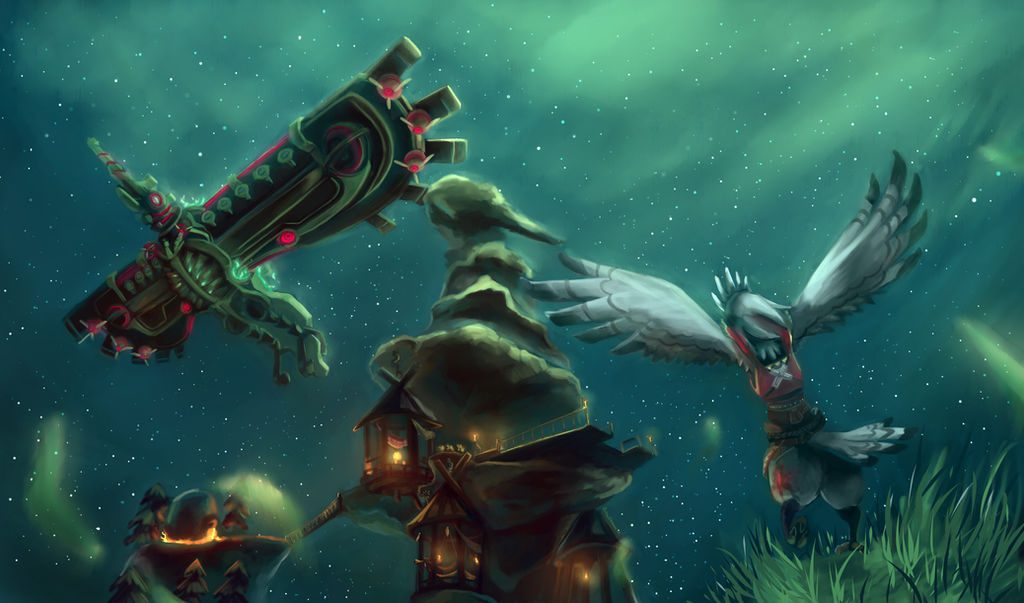

The warrior Rito did not know about all that, though he knew it was beyond foolish to doubt his Chieftan. He had never seen lava up close. But he could see this. Teba glared at the underbelly of Vah Medoh, the Divine Beast supposedly built and commissioned to protect his people long ago. Now the metal monstrosity blocked the sunlight that would have shone on a bird-like race afraid of nothing, except that this was like nothing they had ever seen. The machine’s enormous wings could span the entire village with room to spare. Circles of metal spun furiously under its shoulders. Teba could only assume that was how the giant contraption remained aloft, as its wings never moved -- proof that something so unnatural should never have taken to the sky in the first place.

Va Medoh’s metallic frame narrowed sharply at its front, where a lifelike beak had been fashioned. It did not move. Sound emitted anyway. The screech made Teba’s own warcry seem like the mewling whimpers he had uttered as a hatchling. It shook the warrior Rito to his core. It vibrated the wooden platforms on which he sat, on which his people nursed their wounds. He looked down one flight of stairs and saw, protruding from a blanket, the limp leg and claws of a dead Rito.

Teba’s primaries were made of the same soft white plumage as the rest of him, but the bone and muscles those feathers concealed were powerful. He heard a sharp crack and realized the sturdily built falcon bow he held had snapped in two under the strain of his aimless fury.

Talons clicking on the nearby wooden steps startled Teba out of his emotional reverie. Even in a time of crisis, his people knew not to drop out of the air right next to him. Such an arrival would be akin to breaking down a Hylian’s door. Teba supposed he would have forgiven them in light of this disaster.

He looked up to greet two of his kin. One wore soft brown plumage and bore a feathered spear. The other sported feathers as black as Teba’s were white, a falcon bow gripped in his right wing. Quickly sizing them up, Teba realized with a sigh that the pair symbolized the very dilemma with which his people now grappled. Mezli was deadly with a throwing spear when he had to be, but he always disarmed and captured if the opportunity presented itself. A useful quality, normally, but there was no capturing Vah Medoh. His braided head feathers, a Rito warrior’s source of pride, were sullied with soot and no longer held by twine. The loose feathers were still capped, however, with red metal hooks that resembled the blade of an axe. Mezli was brave, but that bravery was tempered by a patience that held no place in Teba’s heart this day.

Harth, however… had his eyes been the same color as Teba’s, one might have thought they were mirrored pools of revenge. Instead, they shone green beneath a swath of ebony head feathers combed to the side. His braids, like Mezli, were now loose and disheveled. Each Rito sported two, but the number did not matter as much as the ornaments thereon. Harth sported one red bead on each braid, still there thanks to the purple hooks attached to the ends. He was young, but skilled, to have already added beads atop the hooks. More tokens of battles won would come. Teba quietly prayed to Hylia they would come.

He meant to ask them for a report, but instead the Rito captain heard himself say, “My family is safe?”

Appalled at himself, Teba waited to see or even hear the shock at his own betrayal. Flock was greater than mate, chick or roost, and to ask about any of the latter first was to forsake the safety of the flock. Instead of seeing reprobation, however, Teba was startled (and secretly grateful) to see Harth loosen his death-grip on his bow, while Mezli simply sighed and nodded.

“Yes,” Mezli respectfully answered, “they are in one of the caves now, well-hidden.”

Teba could only nod dumbly in reply. Such had been the chaos from Vah Medoh’s sudden attack that he had flown and fought without thought for his wife and eggchick. Perhaps, Teba thought, his action in the moment balanced out his personal priorities in the aftermath. He offered another mental prayer to Hylia in hopes such logic would be received.

Though the village’s stone core was narrow in its middle, caves and passages honeycombed its lake-embedded base and perch-like top. Legend held that “lava” had made such a formation possible, but Teba did not give a chickaloo nut about the truth of that. His family was safe. Time to move on.

“Report,” Teba curtly ordered.

Despite wearing less ornamentation than Harth, it was Mezli who spoke first. Only Hylians thought battles equaled brains. The Rito knew a healthy dose of both was required, even if it took most of young adulthood to realize it. Mezli, the older of the two, spoke first without a hint of surprise or protest from Harth.

“Medoh has ceased fire. Its cannons remain quiet unless any of us fly too close. It appears the beast wants only to control the sky--”

Harth snorted at this, and Teba had to curb his own beak before doing likewise. The thought that anything would win the sky from the Rito was laughable, but Vah Medoh’s shadow seemed to seize that laughter and choke it in their throats. If the machine had indeed decided to rule the firmament, the Rito were as good as the mongrel dogs that Hylians chained outside their houses.

Mezli glanced at Harth, and Teba did the same with slightly more disapproval to bring him back to focus. Lose control now, and the Rito would forfeit much more than the heavens in which they soared.

“Eighteen are dead,” Mezli added heavily. “Fifteen warriors, two nest-makers and a chick.”

Teba’s vision swam for an instant. Not so many had died at once since the Great Calamity, and it was a miracle that more had not perished then. Rito Village lay far enough to the west to avoid the bulk of Ganon’s backblast one hundred years ago. Now, it found itself in the eye of a different storm, one made of metal that spit blue fire. Teba waved Mezli on, again grateful for the older Rito‘s neutral expression. He might as well have been reporting a daily patrol of the village’s eastern bridges that connected it to the mainland. Harth’s fingers had tightened on his bow again, however, his eyes blazing with green fire.

“Kaneli has met with the other elders,” Mezli continued. As leader of the Rito warriors, Teba would have had an equal place among them, but his duties during such an emergency had only just abated enough to allow him to catch his breath, let alone be aware of and attend an emergency council meeting. Such was the catastrophe that it was likely only half the elders had been there, meeting informally. Truly, the Rito ways appeared to be dangling by threads as thin as Harth’s braids. “They will announce it soon in the crevices, but it appears we will be encouraged to wait under cover until Medoh--”

“NO!”

This time Mezli did look shocked, while Harth’s face lit up with fierce hope. Teba did not remember standing up, but he was standing now, his narrow chest heaving against his breastplate with exertion born of fury. His feathers gripped his already broken bow as fiercely as Harth’s.

“We will NOT wait!” Teba shrieked. “We will FIGHT! We will destroy this devil beast and let our chicks play on its carcass! We will not cower as Gerudo vai do from a voe! We will slay the Sheikah beast or die trying!”

Mezli’s face was the picture of utter disbelief now. Warriors never rebelled against the wishes of the elders (though legends said Revali could do just that and already earn forgiveness by the time the elders found out). Even more appalling was to hear a respected Rito disparage another race. Hylians and Gerudo rarely came into the village, but plenty of them passed through the stable built just off the eastern edge of Lake Totori. Odd though their customs might seem, Kaneli had established a multi-generational respect with Hyrule’s other inhabitants.

Teba did not care. His elder was suggesting they cower like chicks terrified of their first storm, seeking the comfort of their nest mother. It was too much.

“I go to fight Vah Medoh,” the Rito warrior said with less fire, more iron. “Will you fly with me?”

This traditional Rito saying was used in countless contexts. Elders offered to allow fledgelings to fly with them so as to learn wisdom. A warrior’s greatest courage, it was said, was needed to ask that question of the nest-maker that had soared into his heart.

This time, however, Teba’s question rang like the tales of Revali’s Company, when the Rito Champion took one hundred warriors to meet the flood of monsters spawned by The Great Calamity. It was said that all had raised their bows and shaken them as one, a wave of feathered death ready to follow its Champion. Teba looked into his brethren’s eyes, however, and saw his commanding plea met half as well as he’d hoped.

“I am with you, flight brother!” Harth harshly cried.

Teba nodded, hoping that the younger Rito was ready for a test far sterner than any he had yet faced. Then his eyes met Mezli’s, and there they found not the scorching fires of battle, but the wet embers of caution.

“We cannot disobey the elders,” Mezli said quietly. “You are my flight brother and my prayers will soar with you and with Hylia, but I will stay to defend the flock.”

Again, Teba nodded, if more abruptly than he normally would have. He did not doubt Mezli’s courage, but he was sorely disappointed that action did not stir in his heart as it did in his own.

“Defend our flock, flight brother,” Teba said through gritted beak. “I go to save it.”

* * *

"Zora's Domain" by Nesskain

Dorephan, King of the Zora, Guardian of the Domain, Will of the Water, sat upon his enormous blue-green throne feeling the opposite of his last honorary title. If he were truly “Will of the Water,” he would order this blasted rain to cease. Instead, it pounded the glass-like surface of his beloved home with maddening consistency.

The Zora were impervious to rain. Even the drenching torrents formed in the Spool Bight to the east were of little consequence to Dorephan’s people. Their rubbery skin and natural ability in the water made storms into playthings for the calves and, occasionally, a still-childish bull. Unless those clouds spit forth lightning. Then, even the bravest bull ran for cover and treated water like poison until the storm had passed.

Thoughts of lightning turned Dorephan’s thoughts to his son. Sidon was a brave bull, enthusiastic to the point of recklessness, but his leadership had already manifested itself magnificently. Dorephan trusted his son as few would at such a young age. Still just one hundred twenty years old, Sidon had already been allowed to explore, track and fight throughout the entire Domain. Even when his son was just an infant, Dorephan had looked forward to the day his Sidon would lead a Zora party the Hylia river, perhaps even to Lake Hylia in the deep south. Such a thought was foolish now. That river skirted too close to Hyrule Castle, where land filth and lizalfos bred. No, the Great Calamity had essentially sealed the Zora to their own waters long ago.

As splendid as his son was, Dorephan worried for him. Testing the patience of an enraged Divine Beast was a good way for a Zora to live as long as a Hylian, especially when that test included shock arrows. Sidon and Seggin had taken what few such shafts could be found in the armory and gone to see if Vah Ruta’s ceaseless torrent could be quenched. Dorephan was grateful for his long life and equally long memory, for only that had provided a glimpse of hope in what was otherwise a hopeless situation. Shock arrows might stop the beast. They also might kill his son.

Dorephan shook his enormous head, which was topped by the silver crown of his station. It resembled a metal sun, complete with seven rays that each contained an arrow-shaped opal. The Zora king was the only one of his people to appear as whale, a rare likeness among the water-bound race. Sidon and Mipha had both taken after their mother, inheriting her dark red skin with the dorsal and tail fins of the fish after which Hylia had created their race. Dorephan fought a rare tear. It had been one hundred years since he had lost his daughter to Vah Ruta. He prayed to Hylia his son would be spared.

As if his prayer had been a summons, Sidon quickly came into view at the top of the gracefully built stairs that led up to the throne room, the roof of which was crowned by a majestically crafted fish of metal bigger than fifty Dorephans put together. The masterpiece overlooked the entire Domain and, before the setting sun dipped below The Veiled Falls to the west, gleamed like an enormous jewel in the twilight. The sun, however, had not shone upon Zora’s Domain in a week, unnatural even for the most water-abundant region of Hyrule.

Sidon strode quickly to the audience circle at the center of the chamber, with ebony-skinned Seggin close behind. For the first time in what seemed hours, Dorephan looked around at The Council ringing the outer walls of the chamber, which had also been waiting for the pair’s return. Many were old, older than Dorephan, even. It was rare for a Zora to join The Council before his two-hundred fiftieth birthday, and that unspoken statute showed in the wrinkled gills of its members. Wise they might be, but even the eldest among them gravely beheld their prince and the former Demon Sergeant.

Truth be told, more eyes focused on the latter, for it was he who had made Dorephan’s plan possible. Seggin was the only one among them to show any resistance to electricity’s fatal touch. Out of necessity, he had been called to serve despite being retired from his position some 50 years previous. Between need and desire -- Seggin might hate Ruta more than any of us, Dorephan thought sadly -- the old warrior had not hesitated to sling a silver Zora bow over his shoulder and nearly leave Sidon behind in his haste.

There was no need for Dorephan to call The Council to attention. Age and respect had already done so, unlike the Hylian meetings he had witnessed in the days leading up to the Great Calamity. The Zora would swim as the water let them, and if the flood proved too great, embrace the water from whence they came.

Dorephan and The Council looked upon Seggin carefully, noting his fatigue and no fewer than five angry scorch marks slashing across his rubbery black skin. Resistant to electricity Seggin might be, but he was still a Zora.

“Sidon. Seggin. We thank Hylia that the waters have brought you home.”

The words were rote, but Dorephan’s tone was anything but. Since he was a young bull, his voice had calmed any within its range, even during the Great Calamity. Mipha had been a curious and energetic calf, but her father’s tone had held her attention or sent her off to sleep with equal ease. The Council visibly relaxed, as did the two Zora in the audience circle.

“Father, we thank Hylia that the waters have brought us home,” Sidon greeted energetically even with a bow of his hammerhead brow. A couple of the younger Coucilfish smiled. The prince may not have inherited his father’s soothing effect, but his zeal would be contagious throughout the kingdom when he reigned. If there was a kingdom left.

“How fared you against Vah Ruta?” Dorephan inquired intently. The attention from the Council seemed to have sharpened, their fin-fringed arms held still so not a word would be missed. “Did the shock arrows succeed as we hoped?”

“Father, we swam to the East Reservoir Lake and approached Ruta from the rear,” Sidon began. “The beast was immediately aware of our presence and began spitting ice at us. I swam around to distract it so that Seggin could have a clear shot.”

Rare murmurs rose from The Council, no doubt betraying their appreciation of the prince’s bravery in the face of near-certain death. Extreme cold was a close second to electricity for the Zora. Eager though he was, Sidon paused his tale to allow order to resume. Dorephan held back a smile. A future king, indeed.

“Seggin targeted one of the red orbs on the beast’s shoulders as you instructed, Father,” Sidon continued. “His aim was true and, sure enough, the water did slow.”

Dorephan leaned forward along with the rest of The Council, though the latter kept quiet after their previous breach in protocol.

“The water, however, soon returned to full force,” Sidon concluded with a definite note of bitterness. “Perhaps because we could not strike it with enough electricity at once. I can only surmise as much after witnessing it myself. Ruta did not stop its assault, and we were forced to cut water.”

Yes, Dorephan thought, he had heard Vah Ruta’s enraged roars, had feared the worst for his son and former Demon Sergeant. “Cutting water” was a last resort among Zora warriors, but when a lizalfo holds the spear and the Zora holds the stick, better to use it as an oar than a sword.

Dorephan settled back into his throne, absentmindedly rubbing the scar on the left side of his prominent forehead. A Guardian had given him that long ago, one of its metallic claws nearly delivering a fatal blow. But The Guardian of the Domain had triumphed with strength only he possessed, hurling the spider-like machine into the ravine between Luto’s Crossing and Oren Bridge and shattering it beyond all repair.

The Zora ruler lifted his fin from his head and stared at it. Even he could not throw a Divine Beast. Hylia’s wings, he could not even wrap his girth around one of the machine’s trunk-like legs. Princess Zelda had once told him that Vah Ruta resembled something called an “elephant,” a beast bigger than a horse that roamed the lands beyond Hyrule. Not that it mattered what it looked like. From squat legs to snake-like snout, the thing needed to be stopped before all of Hyrule drowned.

Dorephan was about to speak these half-formed thoughts when, to his utter amazement, Sidon spoke first.

“Father, I have an idea.”

Fins fluttered in agitation at the boy’s unexpected interruption, but Dorephan knew his son would not usurp protocol without cause. He glanced around at The Council, waited for them to quiet, then nodded toward his heir.

“Seggin’s bravery will be told for countless generations,” Sidon continued, “but it is clear that shock arrows are a danger to even him.”

The former Demon Sergeant went as far as to open his mouth at this, but another glance from Dorephan silenced him. Now was not the time for Seggin to indulge his own stubbornness.

“I believe shock arrows can defeat the beast, but we need someone who can bear enough of them -- and use them safely -- to finish the deed.” Sidon paused, and it was clear to Dorephan that even his confident son was wary of his next words’ portent. “We need a Hylian. I propose we find one and ask him or her to help us.”

For the first time since the Calamity, The Council erupted with unrestrained emotion. The gills of the most elderly vibrated madly, betraying agitation normally reserved for young bulls before their first battle. Seggin, who had dutifully stood behind Sidon during his report, spat on the floor and frothed more spittle as he gave vent to his rage.

“I will have nothing to do with the traitor Hylians!” Seggin hissed. “They are the reason Vah Ruta is here, the reason he showers us with this unending deluge! The reason our Princess Mipha is lost to us!”

Mizu, the Eldest councilman whose head bore a sting ray’s likeness with fading green skin, clenched his withered fist toward the ceiling, his throat pulsating against the silver collar of office that spiraled around his long neck. Others followed suit, leaving Sidon to look helplessly at his father for direction.

“ENOUGH.”

Dorephan did not yell. He did not need to. Speaking just above his natural registers was enough to sound like not-so-distant thunder. The Council was immediately silenced in voice, if not in thought or expression. Seggin still appeared murderous, with the Eldest not far behind.

“Is your grudge worth the lives of the Zora?” Dorephan demanded while turning his great head to take in the room, his voice like a storm rumbling just out of sight. “Not to mention the lives of the Hylians who live just beyond our waters? You will not protest Sidon’s suggestion, not when it is the only course of action currently available to us. If The Council has a better plan, I am eager to hear it.”

More silence followed Dorephan’s words, deflated now that the Council’s protests were revealed to have little substance behind them. The Zora King knew the elders would not change their minds, however. He had only to look upon the statue of his beloved daughter in the plaza below to know that. Their love for Mipha had not been far behind his own, and it had festered rather than waned over a century’s worth of grieving.

“Sidon, I give you leave to search for a Hylian who is able and willing to do this task,” Dorephan announced. “I give you and those who swim with you leave to search wherever there is a whisper of hope.”

Eyes widened at this, but The Council did not dare risk Dorephan’s attention again.

“Avoid Hyrule Castle, but search any area you can safely reach,” the Zora monarch continued. “Arm yourselves as necessary. The Calamity’s essence still lingers, and you will need to survive long enough to find and return with a warrior who will help us.”

Without hesitation, Sidon knelt in the middle of the audience circle, his human-faced and shark-crowned head bowed to the floor while he declared fealty not to his father, but to his king.

“By fin, fish and freshwater, it shall be done.”

Dorephan nodded for the last time, and Sidon immediately bounded to his feet and dashed out of the audience chamber, no doubt keen to find other young Zora who would follow him anywhere. Young bulls and cows had already pledged their hearts to the future king, drawn to him by a charisma matched by none. Sidon would have ample company for the task even without the elders’ support.

The rest of The Council sifted out quietly, many separating into small groups of three or four to discuss what had just transpired. If Sidon did find a Hylian willing to risk his life, Dorephan thought warily, he would have to keep a close eye on his people’s “welcome.”

A young cow struggling to enter the audience chamber snapped the Zora King out of his reverie. The meeting was over, which meant none would bring business to Dorephan unless its nature demanded his attention. Her armor and spear named her a guard of the Domain. A few of The Council glanced at her, but Dorephan paid them no heed. Dunma, daughter of Rivan, was one of the few cows who had not fallen head over fins for Sidon. She would as soon bother her King with something frivolous as she would marry a lizalfo.

The young guard knelt in the circle and remained in that position until Dorephan quietly said, “Report.”

“Your Majesty,” Dunma replied, also quietly, “I apologize for appearing after an Audience, but The Guard felt you should know as soon as possible. The shrine has awakened.”

Dorephan had not thought anything else out of the ordinary could occur on such an extraordinary day, but this news caused huge furrows to appear in his massive forehead that criss-crossed his scar.

“Describe it to me,” Dorephan said calmly.

“It happened only moments ago,” Dunma continued. “One minute it was as lifeless as it had ever been. Now it glows with an orange light. We saw no one around it, nothing that would have caused it. We do not know why, but it shows life now.”

Dorephan had not felt the fingers of fate brush him like this in one hundred years. Vah Ruta, awake and rampaging. The shrine, a long-dead relic of the ancient Sheikah, now alive. What did it all mean?

* * *

Bludo, Patriarch of the Gorons, lumbered slowly across the narrow stone bridges of his beloved Goron City. Molten lava ebbed its way in channels cutting through the only city built on Death Mountain, a testament to the Gorons’ rock-hard toughness. No one else could survive, let alone thrive, in such a place.

The Goron “Boss,” as he was affectionately called by his people, did not walk slowly out of choice. In his younger days as Patriarch, Bludo would stride swiftly and strongly from brother to brother, radiating a strength remarkable even among his people. Years of labor and battle, however, had hunched the once proud Goron. His back, which had once borne the weight of boulders, was now prone to sudden flares of pain that rendered him all but immobile.

Bludo ignored hints of that pain now as he haltingly stumped through his city, taking special care to avoid the newly formed potholes that pockmarked the stone streets. His one good eye focused on an especially deep gouge in the rock, a rough circle still smoldering with bits of lava and ash. Bludo’s people were all but immune to lava and boulders, but when the two were combined into streaking missiles from Death Mountain’s summit, even a Goron was in danger. He made a mental note to tell Fugo about this particular hole, which was deep enough to risk the rock bridge’s collapse.

Lifting his gaze, Bludo watched his rotund brothers living as they would on any other day. Young Krane hefted a cobble crusher, the huge, rough-hewn sword favored by his people. No doubt he was on his way to patrol duty just outside the city gate. His white-haired top knot was held by a thick band of red mountain cloth, the only material not made of stone or metal that could withstand the extraordinary heat. Fugo had finally learned the making of the tricky substance under the tutelage of Master Rohan, the forger who knew more about his craft than any living Goron.

Bludo glanced toward the forge and saw with a smile that Rohan was still sleeping beneath the awning of his hut, which neighbored the great iron anvil upon which he worked. He could create an arsenal of weaponry if necessary, but when it wasn’t, the old blacksmith was just as likely to nap the day away. Fugo had learned quickly, however, that age and sleep did not dent his mentor’s memory. Rohan could wake at any moment and check with unerring accuracy whether his apprentice had accomplished each of the tasks assigned him that day.

The smithy was hemmed in by lava streams on all sides save the stone path that led directly to its entrance. Across the rivulet to its right loomed Bludo’s own rock dwelling, topped by a jagged boulder of obsidian upon which was etched the symbol of his people: the Goron Emblem, portrayed with a golden diamond atop which rested three small, gold triangles. Legend held that the Goron Ruby had once been as real and tangible as the stone on which Bludo now stood, but it had since been given to the legendary hero as a help for his mission many ages ago. The Patriarch had no clue where the Ruby was now, but he’d gladly give one thousand rupees to anyone who could halt the latest threat to his brothers.

A small rumbling from behind caused Bludo to turn around. The tremors were too small to be caused by Vah Rudania or even the infrequent eruptions from Death Mountain. Instead, the Goron chief saw a rough ball of what appeared to be solid rock roll toward him, stop, and unfurl into a young adult member of his people. Pyle’s perfectly round and jet-black eyes -- or the eyes of any Goron, for that matter -- did not convey emotion like those of Hylians. Wide mouths and dark eyebrows did that instead, and right now both of those features conveyed concern on the youngster’s normally cheerful face.

“He’s awake, Boss,” Pyle said worriedly. “Still a lil’ woozy, but the young’un should be just fine.”

“Yer in no place to be callin’ anyone ‘young’un’, young Pyle,” Bludo said gruffly. He softened his words by softly slapping the young Goron on the back, the most oft-used gesture of affection among his rock brothers. “G’on now, git yerself a big bowl o’ obsidian at Tanko’s. Tell ‘im to put it on my tab.”

“Thanks, Boss!” Pyle said cheerfully, his natural good humor restored. In a trice, the young Goron had curled himself back into a ball and was rapidly rolling to the west side of town, no doubt eager to sink his teeth into the rich black mineral.

Bludo turned his attention to the east side of town, where a sprawling hut dominated a large spread of solidified stone surrounded by the largest lava stream. The armory always teemed with activity. Cobble crushers, stone smashers and drillshafts were constantly being made or repaired, a necessity given the Gorons’ endless mining of their beloved mountain.

Lately, however, the rock structure was serving another role. Under its low roof, several Gorons lay sprawled on makeshift beds of stone, all of them sporting bandages made of the same fireproof cloth that held up their top knots. Bludo mentally apologized to Rohan, who was surely napping out of fatigue after churning out so much of the rare material. He would have to thank the old craftsman.

Wounds were an infrequent occurrence among the rock-hard Gorons. On the rare occasion one was suffered, it was usually treated quickly and without much fuss. Newly cooled lava was inserted into the injury and then bound until the damaged area looked just as solid as the rest of the brother’s body. In the wake of Vah Rudania’s rampage, however, a large number of Gorons were forced to wait far longer than usual for the treatment to work. The flying missiles of lava and stone caused painful gouges which required significant amounts of the cooled lava to fill, then heal. No one had died yet, but seeing such vulnerability among the strong people carried a disturbing reminder of their mortality.

There had been no warning or reasoning of Vah Rudania’s madness. The giant metal lizard, which had rested peacefully inside Death Mountain’s crater for a century, had emerged spewing molten rock and fire. Most of the Gorons, mining for precious stones as they always did, were caught in the open. The casualties mounted for two days before the Divine Beast supposedly built to protect the Gorons was finally turned back.

Bludo strode past his wounded brothers toward the back of the armory, where a young but massive Goron sat groggily on the biggest stone bed available. Unlike most of his brethren, Yunobo did not have his white hair in a top knot, but instead wore it loose in a broad, wavy line down the center of his wide yellow head. Enormous hands nearly engulfed that hair now, along with the rest of his face. His wrists and elbows bore bronze bracelets big enough to encircle the head of most Gorons.

“How’re you feelin’, boy?” Bludo gruffly asked.

Yunobo removed his hands from his face. Only his eyes were small, giving his face a very innocent and expressive nature that contrasted greatly with his overwhelming presence.

“I’m all right, Boss,” the youngster replied. He absent-mindedly tugged on the sky blue cloth that encircled his neck, which was tied in a pair of knots below his chin. That cloth had belonged to Yunobo’s grandfather, one of the most legendary Gorons in history. Daruk’s size and strength were a source of pride in Goron City, even one hundred years after Vah Rudania had proven to be the Champion’s demise. Bludo gazed into the face of Daruk’s grandson and saw not the wild bravery of his grandsire, but the preoccupied expression of a far gentler creature. Well, he couldn’t inherit everything from a legend, but he had inherited enough.

“Ya did good out there, boy,” Bludo said encouragingly. “If it weren’t for you, we’d all be done fer, and that’s a fact!”

Yunobo looked up and appeared momentarily cheered. Then the clouds of youthful uncertainty returned.

“It’ll come back, won’t it?” he hesitantly asked.

Bludo nodded, then added bracingly, “Aye, but when it does, we’ll be ready fer it! Between my cannons and yer Protection, we’ll drive that metal beast off as often as we have to!”

Yunobo nodded, then stood. Bludo couldn’t help but admire the youngster, even if he did carry far less fire than his grandfather. When he was small, the Boss’s father had told him of Daruk’s unwavering confidence, which the legendary Goron loved to instill in every brother he saw. Yunobo, on the other hand, seemed in need of borrowed conviction more often than most.

Usually. Now, however, the young Goron stood and pounded his fists together. Immediately, a bright orange shell of… something surrounded him. Through the opaque screen, Bludo could see Yunobo looking around at his magical shield -- the same gift Daruk himself had wielded two generations earlier -- and nod in satisfaction.

“I’ll be ready, Boss!” Yunobo declared with a fair attempt at sounding brave.

For now, Bludo thought, that would do.

***

Icy winds swirled the sand and cloaks around the ankles of two women as they dismounted outside the broad, stone walls of Gerudo Town. The sand seals they had ridden did not shiver, nor did their riders. The former boasted thick fur that by some miracle of Hylia kept them warm at night and cool during the day. The women did not tremble at the cold because they had known the harsh, dual climates of Gerudo Desert their entire lives.

Without a word, they handed off the reins of their mounts to a waiting woman of of considerable height, who then led the bulbous sand seals toward the northwest side of the city. The duo did not follow.Instead they opted for the much shorter walk toward the wall they already faced.

One of them was twice as tall as the other, and she strode very close to and slightly in front of her smaller counterpart’s side as they approached the open arch in the wall that marked the southwest entrance to the city. A guard, another woman, stood sentinel, eyeing the pair carefully until they removed the hoods of their cloaks to reveal sun-darkened skin, bright red hair and emerald eyes similar to her own.

“Sav’saaba,” the guard neutrally greeted.

The taller woman nodded curtly, then strode quickly through the archway, her companion not far behind. It was clear she preferred to walk even faster, but the shorter woman’s gait was clearly setting the pace.

“She did well to keep her wits and not say our names aloud,” the smaller woman noted conversationally. “Remind me to commend her when I see her again, Buliara.”

The taller woman, Buliara, snorted through her large, hawkish nose.

“Lashley does no more than is her duty, Lady Riju,” she said shortly.

Makeela Riju, Chief of the Gerudo, carefully decided not to look askance at her captain of the guard’s coldness toward her own sisters in arms. Buliara was a cold woman, all but wed to the massive claymore she carried because she refused to marry a voe.

More important to Riju, however, was how she herself was viewed by her captain and her people. As the youngest ever to be named chief, she must earn the respect her station implied. To do so, Riju had vowed never to betray any emotion that might be seen as an indulgence to her youth. Impatience, anger, tears, passion, sarcasm. She had shed all of it the moment Buliara delivered news of her mother’s passing, grieving only when none could see.

“Duty is difficult in the face of disaster,” Riju said, still in that casual tone. She wondered if Buliara had ever snorted at her mother. She doubted it. “She remembered to ignore ceremony and prioritized secrecy despite being stationed in plain view of Vah Naboris, a sight that would cause many to panic.”

“She would not be part of the Guard if she were prone to panic,” Buliara answered crisply. A pause, then she added in a softer, albeit still gruff, tone, “I will remind you as you have asked, Lady Riju.”

The young chieftain made sure to nod without the slightest hint of satisfaction, though she felt it blossom in her exposed stomach. Riju had temporarily discarded her royal skirts and silk, sleeveless top in favor of the more practical, voluminous pants and tightly bound halter worn by most Gerudo. Her long red hair, normally worn loose beneath the golden Scarab Crown, was tightly bound in one long braid. It was far easier to sand surf that way.

The two continued their purposeful path through the night-shrouded city, silent save for the soft murmuring of water running swiftly through straight, raised channels of the same stone that composed the outer walls. The ancestors alone knew how such a miracle had come to be, but the presence of water had, according to the histories, allowed the Gerudo to cease their nomadic lifestyle. Here they had built their white stone city, in the middle of the vast Gerudo Desert that swallowed the southwestern portion of Hyrule. Only one path led directly to the four-walled town, a winding dirt track packed down from the steady use of travelers on foot since no horse could survive the harsh climes of the region. It ran northeast, toward and between the snow-capped Gerudo Highlands to the north and Spectacle Rock with its accompanying mesas to the east.

Inside the city, the small alley in which the pair walked spilled into a central plaza, where renowned Gerudo vendors sold their wares every day. Gerudo traveled for two reasons: goods and voe, and that was enough to ensure many of them were always out and about in Hyrule. That meant a steady stream of business flowing into and out of their homeland, to which its people -- and female members of other races who braved the journey -- flocked daily.

At night, however, the square was silent. Neither chief nor captain took any chances, clinging to the shadows along the closed and shaded storefronts until they were forced to ascend a broad set of stone steps at the northern side of the square. They did so swiftly, not stopping as they usually did at the first landing that led to the royal courtroom, but rather continuing up a second flight all the way to Riju’s private chambers.

A giant bed, made and waiting for its owner’s rest, sat with curtains drawn on a raised square of stone in the center of the room. Stone walls with shelves carved into them framed the chamber. Taking up much of the floor space were richly colored carpets and -- most impressive of all -- a small channel of water running parallel to the bed platform’s left side, continuously fed by seal-shaped fountains built into the back wall.

Just in front of the bed squatted a stone couch made soft with colorful cushions, blankets and pillows. There Riju sat down, finally acknowledging the fatigue and stress of her journey with one long sigh.

Buliara began pacing in front of the couch. Between her and her chief sat a small stone table on which rested an open book and plush toy made to look like a sand seal. In as casual manner as possible, Riju closed the book. She could allow her captain of the guard to see the toy, a gift from her mother when she was small. She could not bear, however, the thought of Buliara glimpsing her diary, the only emotional outlet she allowed herself.

Back and forth the muscular Gerudo paced until, unable to restrain herself, she stopped to face her chief and give vent to what Riju knew was coming.

“You could have been killed!” Buliara hurled the words like a lash, though she kept them to a hoarse whisper so as to keep them private from the most unlikely of passerby. “What good would you be to the Gerudo dead? You have no daughter! No heir to the throne! If your mother knew where you went tonight, what you did, you would be striped like a girl half your age!”

Riju let the words wash over her, understanding that anger was not the only emotion feeding heat to that voice. Buliara was not motherly, but Riju knew she viewed herself as the most mother-like presence in her life, now. This was the only reason she forgave her captain for this outburst, but she must be careful. Allow this to carry on too long, and the line between fierce, motherly concern and captainly duty would become blurred beyond saving.

“I did what I felt was necessary for my people, Buliara,” Riju said, more calmly than conversationally this time. “We must know what we are facing.”

“Then send me, or another of the Guard to investigate,” Buliara moaned. “Anyone but yourself! You are too important! You must learn to delegate so that--”

“Stop whining, Buliara,” Riju cut her off curtly, with just the proper amount of disdain. “Keep it up, and I shall think you are pining for a voe’s touch.”

Buliara’s eyes widened until they were the size of saucers. Riju stifled an inward giggle. Were it not for her captain’s vicious independence and propensity with all manner of weaponry, a voe might indeed find her striking.

“I went,” Riju continued before Buliara could recover, “because I am the best sand seal rider among our people. No other could surf through the storm Vah Naboris stirs. I saw what we needed to know, and that alone was worth the risk.”

Visibly chastened, Buliara swallowed her previously formed words and, gathering what propriety remained her, asked, “And what did you learn, Lady Riju?”

“That if it came to Gerudo Town, we would be helpless,” the young chief said flatly. “It spit forth sand and lightning the moment I got close. Were it not for Patricia’s speed, I would be as dead as you feared. If Naboris comes here, I’m afraid all of us will be.”

Buliara swallowed, then asked with a note of respect Riju felt was a marked improvement from her earlier tone.

“How did you come to be as I found you, unconscious in the sand?”

“Once I ascertained the threat of Naboris, I made to return straight away.” Riju thought it slightly unnecessary to comfort Buliara this way, but she had already been dealt a blow of authority. Her mother had taught her that not sparing the whip was important, but not sparing the hydromelon juice afterward was no less so. “Unfortunately we ran into a pack of bokoblins while still fleeing Naboris’ storm. Patricia balked and pitched me into the sand. That is the last thing I remember before you found me.”

There was an awkward pause at this, for both women knew that had one not found the other, the Gerudo might indeed be without a chief. The night cold alone could kill a person not keeping his or her blood moving, and if that didn’t, bokoblins or lizalfos or -- ancestors forbid -- a molduga surely would.

The moment passed. Buliara straightened her stance and then, causing Riju to experience another small thrill of royal victory, responded as she would in the royal court.

“I am pleased that you are not harmed, Lady Riju,” the Captain of the Guard said militantly. “What is it that you command?”

The young chieftain was about to respond when a clamor from below grabbed her attention and made Buliara immediately unsheathe her enormous sword. With strength superior to most voe, the warrior Gerudo picked up her diminutive charge with one arm and hurled her some 10 feet to the bed before turning to face the entryway, blade raised and emerald eyes alight with battle fire.

“Captain Buliara! Lady Riju!”

The voices, clearly those of her own people, caused Buliara to lower her blade slightly, though her eyes narrowed. Riju knew what she was thinking. Gerudo guards barging noisily into her private chambers in the dead of night? Something was wrong. Riju rose and stood beside the bed, well behind Buliara so it was clear they would answer to her captain first, but close enough to make their Chieftain's presence felt.

Barely had the pair of Gerudo soldiers breached the doorway when Buliara immediately called them to attention.

“Stand and report!” she ordered harshly.

Though they had undoubtedly sprinted up the stairway, neither Gerudo was breathing hard due to their extraordinary physiques. If a Gerudo guard was tired, she was likely on the doorstep of death. Both wore their red hair in high ponytails similar to Buliara’s, but only one removed the veil covering her mouth to answer.

“Captain Buliara, the Thunder Helm has been stolen!”

Riju was not aware of sitting down, but she found herself once again seated on the couch just the same. Before the guards’ arrival, her next words to her captain were completely centered on the ancient relic of her people, handed down from generation to generation. Worse, losing it meant losing the tangible symbol of her family’s rule. Would the Gerudo follow Makeela Riju, the Chief who lost the Thunder Helm?

Spoken words began to pierce Riju’s inner wonderings.

“It must have happened no earlier than two hours ago, Captain.” One of the guards was answering a murderous-looking Buliara. “We do not know who or how, only that when we arrived for our watch, the helm was gone. The previous guards were questioned and searched, but they do not know the whereabouts of the Helm.”

“We’ll see about that!” Buliara snarled.

“Buliara!”

Halfway to the doorway, the Gerudo captain stopped, arrested by the stern tone of her Chief. Riju had risen from her bed and walked swiftly toward them, so that she now looked directly up at Buliara. Curse the sands, but I wish I was taller! Discarding the notion for the umpteenth time, Riju continued.

“You will not harm the guards in question, Buliara,” Riju commanded. And it was a command. The actions of Divine Beasts and thieves were not her fault, but she would die before allowing her captain to sew distrust among her people. “You will question them. You will explain why you must search their homes before you do so. After that, you will bring them before me, so I may ask them about the Helm and how you treated them.”

Buliara’s throat constricted, but she swallowed and nodded. Riju returned the nod, and that was all the permission her captain needed to resume her flight through the doorway, followed closely by the guards who had delivered the news.

Alone for the first time since Buliara had found her, Riju sank into her couch, hugging her toy sand seal tightly to her chest. Oh Mother, she desperately thought, have I failed already?

* * *

The old man stood up with a groan, his back knuckling as he stretched to fully wake himself from the unplanned nap he had taken at the base of a thick chickaloo tree. A squirrel, no doubt searching for one of the tree’s namesake nuts, scampered away at the unexpected interruption.

Thick trousers and boots, a shirt and vest, heavy cloak and woolen gloves kept all but the man’s face covered, and even that was shrouded by a magnificently thick, white beard. Above it rested a broad nose, soft amber eyes and thick, white eyebrows. He gazed skyward to gauge the sun’s position, which was nearly at its noon peak. Nodding to himself, he gathered a half-full haversack and a staff nearly as tall as himself. Tying the haversack to his broad leather belt and the axe to his back, the old man used the staff to assist his short walk from the forest up a short path that cut its way through short wild grass and up a sizeable hillside.

His eyes rested briefly on the high side of the hill where the path ended, but he would not be going that far. Instead, he halted about halfway up, where a collection of slabbed stone formed a small overhang. He saw with satisfaction that the small pile of wood he had left there some days earlier was still there, undisturbed. Unpacking his supplies, the old man kindled a fire and once again rested his weary body, this time against the inside of the stone lean-to. After digging out an apple from the haversack, he deftly whittled the end of a nearby branch down to a sharp point, upon which he stuck the apple and lazily propped it over the fire.

The old man’s eyes closed briefly, but he was careful not to fall asleep. He kept his gaze lazily focused on the path that led up the hill, waiting to see what one hundred years’ worth of patience would bring. Soon, he would have to wait no longer. Soon.

* * *

This the first of a six-book series based on The Legend of Zelda: of the Wild.