Change and Return: A Pitch for A Link to the Past 2’s Story

Posted on May 24 2013 by Legacy Staff

Let’s talk about stories.

Let’s talk about stories.

To those of you familiar with my article work on this site, you will know that I have a deep passion for storytelling, and specifically, story structure. I’ve written about the monomyth — or, as it is more commonly called, the “Hero’s Journey” — and how this literary phenomenon is reflected within the Zelda series. I’ve talked at length about Joseph Campbell’s theories and their pertinence to both the series and video gaming at large. It is safe to say that most of my work here has been an exploration of storytelling in the Zelda series, and I would venture to say that I am one of the most ardent defenders of the series in this respect.

That said: Nintendo, it’s time to step it up. Gaming has evolved, and on the whole, the medium is maturing at a rate far faster than you are. Storytelling in games has reached new heights, with behemoth titles like Journey (another game I’ve talked about here) and BioShock Infinite doing some exciting things with the medium in ways both new and conventional. Games aren’t just about gameplay anymore; they’ve turned into a versatile and powerful storytelling medium. And, Nintendo, you’re being left behind.

But not all is lost. Long have you been the titan of gameplay, the company that manages to make games fun even when their stories are inane or razor thin. You can retain that crown while moving forward into gaming’s new future as a storytelling giant. You have the perfect opportunity sitting in front of you, too: A Link to the Past 2.

This is a call to arms. This is a humble, but passionate, pitch for pushing your own storytelling forward, Nintendo. Today, I am going to talk once again about the Hero’s Journey, and how you have a wonderful chance to use this new game, this new chapter in a legendary franchise, to tell a fantastic story that you’ve already been telling. You just didn’t know you were telling it.

The Hero’s Journey, revisited

We’ve come back to this topic a few times, and it can never hurt to have a bit of a refresher. But every time we come back here, we also talk about a new aspect, or an old aspect in greater depth. Today, we’re going to explore circles. One of the most frequently discussed aspect of the monomyth, and Joseph Campbell’s initial theory discussed this as well, is the idea of the Hero’s Journey as a circle. Many different people have talked about this since the initial theory was discussed, and each of them has put their own spins on his theories. The expanded version of Campbell’s theories that I find most developed and most useful is Dan Harmon’s. Dan Harmon, the creator of NBC’s sitcom Community, has an extensive series of pages that lay out his full theories, all of which are heavily rooted in Joseph Campbell’s own. I highly recommend that any writers and anybody with even a passing interest in story structure check out the entire series, as I am going to only briefly describe his ideas here.

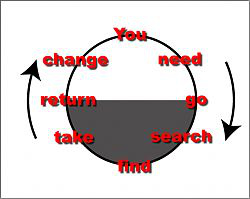

We start, naturally, with a circle.

At the top of the circle is the protagonist in his normal state at the beginning of the story. For the sake of ease and since we’re talking primarily about video games here, we’re going to refer to him as “you”.

Now something happens, or may have already happened, and you are no longer content. You are called to adventure (this is the same “call to adventure” that we discussed last time!). Though you may not know it, you are called to adventure because you need something, whether you know what it is that you need or not. This is the top right part of the circle.

The call to adventure is the need. Accepting the call — as all heroes will — is going off in search of what it is that you need. Again, you may not know what it is you need. But answering the call and going off on an adventure is going in search of it. You are leaving your natural state. This is the beginning of the descent phase of the journey, and lies on the rightmost point of the circle.

Having left your comfort zone, and traveled into the unknown (represented by the darkened lower half of the circle, as opposed to the known, represented by the white upper half), you begin to search for that something, or to find out what the something is and then search for it. This is the bottom right part of the circle.

Having left your comfort zone, and traveled into the unknown (represented by the darkened lower half of the circle, as opposed to the known, represented by the white upper half), you begin to search for that something, or to find out what the something is and then search for it. This is the bottom right part of the circle.

Eventually, you find it. At this point, you’ve come a long way from home at the top of the circle, and are firmly entrenched in the unknown. This is as far as you go, however, because you’ve found what you were searching for, and now have to begin the long journey back up the circle: The return phase that follows the end of the descent.

Having found what you’re looking for, you now have to take it, and this involves paying some sort of price. You have to suffer some affliction. You have to atone, as Campbell put it. Once you’ve done that, you’re ready to move on with the thing that you were seeking from the start. This is the bottom left of the circle.

Now, you return back to where you started, emerging back from the unknown into the known, as your journey comes to a close. But simply returning isn’t enough: You return, with the critical difference of having changed in the process of finding the object you were searching for. You don’t make it all the way back up to “you”, because you’re no longer the same person you were when you started; you’ve changed. This is why change is only the top left part of the circle, rather than back at the top; you aren’t the same “you” anymore, but rather a brand new “you”.

For those of you familiar with the Hero’s Journey already, this probably sounds intimately familiar, if a bit more general and less fantastic. The three things I really want to spotlight here are the circular aspect of the model, the cycle of descent and return, and the gap between the initial hero and the changed hero. The circular aspect creates a certain symmetry to the whole experience; events as we travel back up the circle are going to resemble events as we traveled down the circle. This symmetry is reflected in the cycle of descent and return that marks the whole affair. The only part where the circle breaks is the gap at the very end: We don’t quite make it all the way back to where we started, because the hero has changed. He’s got what he needed, however, and that’s close enough to full circle.

We’re going to be talking about these in greater depth here shortly, but for now, just be aware of them: The journey is circular, is a cycle of descent and return, and there is a gap between the changed hero and the initial hero. Got it? Great. Now let’s talk about Zelda.

Timeline Theory and the “Hero of Light”

Back before the days of the official timeline, there were heated and engaging debates regarding the official chronology of the series. Because the games are intended to be experienced mostly separate of each other, rather than as a connected whole, there were precious few bits of information that we as theorists could latch onto in order to assemble a tentative timeline for the series. There were a few pieces, however, that were mutually agreed upon as taking place in a very specific order. Most of these were due to direct statements in game manuals and box art as well as developer quotes. One of the most consistently accepted pieces of the timeline was a series of six games, starting with A Link to the Past.

Back before the days of the official timeline, there were heated and engaging debates regarding the official chronology of the series. Because the games are intended to be experienced mostly separate of each other, rather than as a connected whole, there were precious few bits of information that we as theorists could latch onto in order to assemble a tentative timeline for the series. There were a few pieces, however, that were mutually agreed upon as taking place in a very specific order. Most of these were due to direct statements in game manuals and box art as well as developer quotes. One of the most consistently accepted pieces of the timeline was a series of six games, starting with A Link to the Past.

A Link to the Past, originally released for the Super Nintendo in 1991 in Japan, was — as its name implies — billed as a prequel to the two existing titles in the series, The Legend of Zelda and Zelda II: The Adventure of Link. This fit easily: A Link to the Past was chronologically the first game in the series, with The Legend of Zelda and The Adventure of Link following sometime thereafter. Then, in 1993, a GameBoy Zelda title appeared: Link’s Awakening. This game, which started out as a port of A Link to the Past, used many of the same art assets as the original Super Nintendo title, despite eventually growing into an original project with an original story. Because it didn’t take place within Hyrule — but rather on the dreamed island of Koholint — this game had no direct impact on the chronology currently in place, but was generally agreed to be a sequel to A Link to the Past.

Years later, the games Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons arrived on the scene, and fit into the timeline wonderfully. Developed at the same time, the two games featured a unique system called “Linked Game”, in which the player — having beaten one of the two games — could enter a code at the beginning of a game and experience an altered version of the story with references to the previous game as well as an additional, bonus ending. This allowed the two games to work together to tell a single story in two parts. Both games began the same way: with Link entering the chamber of the Triforce and falling into Labrynna or Holodrum (in Ages or Seasons respectively). Given that Link had saved Hyrule and acquired the full Triforce as an unbroken whole in A Link to the Past, this meant the two Oracle titles could be slotted — as an entire two-game story — right after A Link to the Past. As for Link’s Awakening? Well, the ending of the Linked Game feature of the Oracle titles features Link sailing out to sea on a raft — exactly how Link’s Awakening begins. This was a perfect fit, giving us a nice unbroken stream of six games: A Link to the Past, immediately followed by Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons, immediately followed by Link’s Awakening, followed hundreds of years later with The Legend of Zelda and its direct sequel The Adventure of Link.

This timeline was agreed upon well before the publication of Hyrule Historia, which confirmed this timeline as accurate. Even though it would have been easier to simply cite that book as evidence that these games fit in sequence like this, I explained how the Zelda community came to agree upon this to illustrate a simple fact: These games are telling a connected story. It’s not simply the word of an encyclopedia that makes these games officially chronological. These games fit in sequence because they are clearly and self-evidently part of the same story.

Now, why is this important? Well, if we look a bit closer at this sequence of six games, we can see that there are, in fact, only two different individuals known as Link throughout the entire six game streak. There is a single Link who first appeared in A Link to the Past, and then is featured once again in both Oracle titles and Link’s Awakening, and then there is the Link who stars in The Legend of Zelda and The Adventure of Link. These two Links are the principal actors in a large story that takes place over multiple games.

I want to look at this first Link, a Link that I am going to call the “Hero of Light” (he was never given an official title, but I will give him this one to differentiate him from the other Links of the series). This is a Link whose story began in A Link to the Past and continued over three additional games. This is a Link who was thrust into adventure over and over again, and measured up to the task each and every time. But most importantly, this is a Link with a single story to be told: the story of a hero cast away from his home, and forced to find his way back, facing countless trials and tribulations along the way. This is a story told in four parts, and one that still is not yet complete.

The Hero of Light, in each game that he starred in, embarked upon the Hero’s Journey. But his larger journey, the one that has taken four games and will take at least one more to complete, is itself a much larger and more complete example of the Hero’s Journey. It is this larger narrative, the one that runs throughout all four games, that I want to discuss today.

The Journey of the Hero of Light

So now we’re back to the Hero’s Journey. Remember that the entire circle is ultimately a cycle of descent and return. The hero descends into the unknown, and returns from the other end a changed person. So we can split this into two segments: The descent, and the return. But we actually need to add one more segment to this, as it is fairly critical: We need to describe our hero’s natural state. What exactly is the hero’s state at the top of the circle? What is his natural environment, his position at the beginning of our tale? This is a segment that we can’t ignore, as if we don’t have this baseline, then his journey isn’t as meaningful. The journey is a departure from this normal state, and if we don’t establish that first, then the departure isn’t as significant. As such, we must add an additional segment, in which the story establishes this normal state of the hero: For our purposes, this is the segment where Link becomes the hero of Hyrule. So we have three clearly defined segments: Becoming the hero, the hero descends, and the hero returns. The journey of the Hero of Light begins with A Link to the Past, which forms the first segment: Becoming the hero.

So now we’re back to the Hero’s Journey. Remember that the entire circle is ultimately a cycle of descent and return. The hero descends into the unknown, and returns from the other end a changed person. So we can split this into two segments: The descent, and the return. But we actually need to add one more segment to this, as it is fairly critical: We need to describe our hero’s natural state. What exactly is the hero’s state at the top of the circle? What is his natural environment, his position at the beginning of our tale? This is a segment that we can’t ignore, as if we don’t have this baseline, then his journey isn’t as meaningful. The journey is a departure from this normal state, and if we don’t establish that first, then the departure isn’t as significant. As such, we must add an additional segment, in which the story establishes this normal state of the hero: For our purposes, this is the segment where Link becomes the hero of Hyrule. So we have three clearly defined segments: Becoming the hero, the hero descends, and the hero returns. The journey of the Hero of Light begins with A Link to the Past, which forms the first segment: Becoming the hero.

There’s not really too much to say about A Link to the Past in this regard. The entire plot of the game involves Link proving himself. First, he has to prove himself to the Master Sword by gathering the Pendants of Virtue. Master Sword in hand, he travels to defeat the wizard Agahnim and rescue Zelda, but arrives too late. Though he defeats the wizard, he is trapped in the Dark World. Then he has to prove himself to the Maidens by freeing them from their captors in the Dark World so that he can defeat Ganon. But to defeat Ganon he first has to find the Silver Arrows, the only weapon capable of killing the beast. All throughout the game, Link is performing these great feats as a way of proving his worth. One is reminded of the mythical twelve labors of Heracles, undertaken in order to reacquire his godhood. A Link to the Past, by focusing on this need for Link to prove himself, is very much a tale about becoming the hero that Hyrule needs. In the grander tale of the Hero of Light, A Link to the Past is simply the “you” stage at the top of the circle. Though Link undergoes the full Hero’s Journey within the game’s own story, as part of this larger tale it is simply setting the stage for what is to come.

Having established how Link became the hero and arrived at the “you” stage on top of the circle, the story now moves on to the hero’s descent. This begins in the Oracle titles in a very literal way: The shared opening of the games has Link literally fall — or descend — into the new worlds in which they take place. Immediately, however, the question is why this happened. Why did the Triforce see fit to send you into these new worlds to carry out some task? Why were you called to adventure? What did you need? The answer doesn’t come until later, at the end of the Linked Game, when Zelda tells you the reason for your journey.

So why was Link called to this adventure? Because the Triforce dictated that Link needed to become a legendary hero. Now, we had already established in A Link to the Past that Link was a hero. But the Triforce did not play a part in Link’s heroism throughout the game. No, the Triforce was in Ganon’s possession, and only became an element for Link at the very end of the game. Having bested the evil that was Ganon, Link had become a hero in the eyes of Hyrule, but not in the eyes of the Triforce. So the Triforce sent Link on another journey, one in which he proved himself in all three aspects of the Triforce. It is no coincidence that the three Oracles — Ages, Seasons, and Secrets (this Oracle is an NPC in the Maku Tree in both games, rather than a focal point of her own game) — share the names of the three goddesses: Nayru, Din, and Farore, respectively. Link was tasked with saving the Oracles in order to prove himself worthy of being the legendary hero of the Triforce.

Link needed to become a legendary hero in the eyes of the Triforce, so he went to Holodrum and Labrynna, searched for the Essences of Nature and Time (respectively) and saved the Oracles, and found that he was worthy of becoming this legendary hero. That brings us all the way to the bottom of the circle. Before we move on, there is one thing I want to point out: Other than the Triforce deeming it necessary, we as players are not currently sure why exactly Link needed to become this legendary hero. It wasn’t to stop the resurrection of Ganon, since he indirectly caused that with his very presence (Veran would never have been able to possess Nayru in the opening of Oracle of Ages had Link not moved the rock with the Triforce on it for Impa). We’re missing the reasoning behind Link’s need to become the legendary hero. We’re going to address this soon, so keep it in the back of your head for now.

Having saved the world from the partially resurrected Ganon yet again, Link left Holodrum and Labrynna behind, sailing out to sea in search of new lands. As he travels by raft across the sea, he gets swept up into a massive storm, eventually washing up on the shores of the mysterious Koholint Island. He learns, from a mysterious Owl native to the island, that if he wishes to leave Koholint Island he will need to awaken the Wind Fish by gathering the eight Instruments of the Sirens and playing the Ballad of the Wind Fish. Naturally, Link accomplishes this task, and learns that the entire island was the dream of the Wind Fish, and that his adventure had been entirely within that dream. Having defeated the Nightmare that infested the dream and awakened the dreamer, the island fades, and Link continues his voyage home.

This segment of the larger tale of the Hero of Light seems almost entirely unrelated, but I would argue that this is one of the most critical moments in the journey. This is the one stage so far where Link is not proving himself to anybody: He is acting completely of his own accord, acting upon his desire to get off the island and return to Hyrule. But his concern for the people of Koholint, and his giving aid to these people, is a sign that he has taken the role of legendary hero in stride, and has truly become that hero. He is no longer working to prove himself, as he has already done so: He found what he needed. He’s now made it to the take stage, where he must pay the price of having proven himself as the legendary hero of the Triforce.

This segment of the larger tale of the Hero of Light seems almost entirely unrelated, but I would argue that this is one of the most critical moments in the journey. This is the one stage so far where Link is not proving himself to anybody: He is acting completely of his own accord, acting upon his desire to get off the island and return to Hyrule. But his concern for the people of Koholint, and his giving aid to these people, is a sign that he has taken the role of legendary hero in stride, and has truly become that hero. He is no longer working to prove himself, as he has already done so: He found what he needed. He’s now made it to the take stage, where he must pay the price of having proven himself as the legendary hero of the Triforce.

We’re shown that through the final boss of the game: The Nightmare, a collection of past foes that Link has fought. All of them are old bosses from A Link to the Past (some of which reappeared on the island), and two of them are Agahnim and Ganon themselves. Agahnim and Ganon had not reappeared on the rest of Koholint Island, so their appearance here indicates that the Nightmare is drawing upon the experience of Link, rather than simply the dream of the Wind Fish. The Nightmare’s reflection of these specific enemies points to a certain fear within Link: His past experiences, his past adventures, have created emotional scars for him. He still has the courage necessary to face those fears, and that is ultimately the most important factor, but the fears are definitely there. This is the price that Link has paid for becoming the legendary hero.

We’re beginning to see the full picture here: Link became a hero in A Link to the Past. From there, the Triforce tested him and groomed him into a legendary hero through the events of Oracle of Ages and Oracle of Seasons. Having faced and conquered these challenges, he began the journey home, with the events of Link’s Awakening providing him a way to directly interact with the fears and anxieties that his journey has left him scarred with in the process of turning him into a hero. He has become a hero, and he has completed his descent.

We’re only missing one more step in this great journey of the Hero of Light: The return home.

A Link to the Past 2: The Hero Returns

Still with me? Good!

We’ve talked about a lot since, but recall the beginning of this article. I said that Nintendo has a unique chance to finish a story that they didn’t know they were telling. Now that we’ve arrived here, it’s time to talk about how they can do just that. Nintendo has woven this exciting adventure for the Hero of Light through four games, and with this game it’s time to end the story in a satisfying fashion that deals with the part of the Hero’s Journey that most stories only ever touch upon.

A Link to the Past 2 has been confirmed to take place within Hyrule: Specifically, the Hyrule of A Link to the Past. Gameplay footage suggests that it takes place within the exact same Hyrule, down to the smallest of details. At first, I — and many other fans — were skeptical about this, wondering how exciting exploring the same region from a previous game could be, even if the dungeons were different. But as I thought about it, I realized that Nintendo could be on to something major here.

A Link to the Past 2 has been confirmed to take place within Hyrule: Specifically, the Hyrule of A Link to the Past. Gameplay footage suggests that it takes place within the exact same Hyrule, down to the smallest of details. At first, I — and many other fans — were skeptical about this, wondering how exciting exploring the same region from a previous game could be, even if the dungeons were different. But as I thought about it, I realized that Nintendo could be on to something major here.

Link has changed throughout his journey through Holodrum, Labrynna, and Koholint, this much is undeniable. But during that time, Hyrule wasn’t standing still: No, Hyrule, too, was changing. Though the Hero’s Journey focuses primarily on the change that the hero undergoes, it is very common that the world itself will change along with the hero. The Hyrule that our hero will be returning to is not the Hyrule that he left. Sure, the geography of it will be the same. But the people will have changed. The monsters and enemies that populate the country will have changed. Hyrule, at this stage, is still a living and breathing kingdom, a far cry from the desolate wastes that mark The Legend of Zelda a few hundred years down the line. It’s changing along with Link. Being able to explore a changed Hyrule that nonetheless feels intimately familiar is an exciting opportunity. If Nintendo can capture that feeling of things being out of place upon your return to a place you once knew, they have a chance to create a powerfully engaging gameplay experience.

Indeed, the entire story and character interactions should be structured around the gap between “change” and “you” at the top of the circle. A hero who returns doesn’t feel at home anymore: They’ve been forever changed by their journey, after all. Link, who has been gone for so long, should not feel at home in this changed Hyrule. NPCs should treat him with something similar to hostility. He’s not as welcome as he once was, and everybody approaches him with an odd caution. He stands out in cities and people avoid him. The royal family has replaced him, and they have a new guardian. And all the while, a new threat is rising.

Remember that we weren’t sure why Link needed to become the legendary hero that the Triforce wanted him to be? Well, this is precisely why. There is a new evil brewing in Hyrule, one that is different from anything Link has faced before. It’s not Ganon this time, and he can’t be defeated simply with Silver Arrows. This is a new villain for this new Hyrule, and Link should have a steep learning curve in terms of determining how to deal with this menace. The villain should be able to reach the first stage of his plan unimpeded, as Link, beset with a bizarre out-of-placeness, will be unable to devise a way to stop the evil. Having reached one of his goals, the villain moves toward his endgame. Link attempts to stop him, perhaps brandishing the Master Sword or the Silver Arrows as before, but these weapons of old are ineffective. Something new is required, and Link is having difficulty adapting to this. Only after he has tried and failed to use the old ways to defeat this new menace should Link move on. This idea of the villain being a product of the changed Hyrule, and Link, having changed in different ways, being unable to adapt as necessary to defeat this villain readily, will drive home this idea of change and the strangeness of a hero’s return.

Remember that we weren’t sure why Link needed to become the legendary hero that the Triforce wanted him to be? Well, this is precisely why. There is a new evil brewing in Hyrule, one that is different from anything Link has faced before. It’s not Ganon this time, and he can’t be defeated simply with Silver Arrows. This is a new villain for this new Hyrule, and Link should have a steep learning curve in terms of determining how to deal with this menace. The villain should be able to reach the first stage of his plan unimpeded, as Link, beset with a bizarre out-of-placeness, will be unable to devise a way to stop the evil. Having reached one of his goals, the villain moves toward his endgame. Link attempts to stop him, perhaps brandishing the Master Sword or the Silver Arrows as before, but these weapons of old are ineffective. Something new is required, and Link is having difficulty adapting to this. Only after he has tried and failed to use the old ways to defeat this new menace should Link move on. This idea of the villain being a product of the changed Hyrule, and Link, having changed in different ways, being unable to adapt as necessary to defeat this villain readily, will drive home this idea of change and the strangeness of a hero’s return.

But let’s take it further than that. We, as longtime players of this series, are very familiar with the way that the games are designed. We have the series distilled to a basic formula, and can spot when the games do familiar things like introduce elements in the overworld that require an item we will acquire in the next dungeon. These are things that we’ve picked up on by playing so many games in the series. As gamers, we have changed. We’ve learned. Just as Link’s ability has grown throughout his journey, our abilities and skill within the series have grown in a very significant way.

Now is the perfect time to pull the rug out from under us. As the story of the game emphasizes that Link is out of place, this game should make us feel out of place. Give us variations on old items that, though our experience with the series would lead us to conclude that one way is the correct way to solve the puzzle, it is in fact not the correct way, and we have to think differently in order to solve it. Give us slight variations on the overworld/dungeon system that feel somewhat jarring and perhaps even not Zelda-like. Make us feel outdated and behind the times. Give us that same feeling that Link has of being left behind while the rest of the world has changed. Our old methods won’t work for us anymore, so we would have to adapt. Make the gameplay reflect the central idea of the game: You’ve changed one way, but the world has changed as well, and you don’t belong here anymore.

Nintendo has this wonderful chance to really drill into the core of the return home, a stage of the journey that is often overlooked. Far too often do I see heroes simply return to their point of origin and live out their days happily ever after. But how can they? If the experience is meaningful and transformative, they are fundamentally different people at the end of their journey than they were at the beginning. Nintendo can show us why these heroes aren’t going to feel at home anymore. A Link to the Past 2 can be a game about return and change, and the gap between the hero departing and the hero returning.

Finish your story, Nintendo. And do it right.