Balancing Act: A Game Designer’s Challenge

Posted on January 07 2011 by Legacy Staff

There’s a saying that “You can’t please everyone.” Yet this is often the challenge game designers face in the process of creating a game: to release a game that appeals to a wide variety of players, from young to old, from new gamers to veterans.

There’s a saying that “You can’t please everyone.” Yet this is often the challenge game designers face in the process of creating a game: to release a game that appeals to a wide variety of players, from young to old, from new gamers to veterans.

When it came time to begin designing Ocarina of Time, it’s not hard to imagine that there were many challenges in transitioning the game play from 2D to 3D. One advantage, however, is easy to overlook: The release of Ocarina of Time was the closest the series will probably ever come to starting each player out on the same level. Things that we take for granted now, like Z-targeting, were innovations to the game that players old and new had to get used to. While nowadays players may complain about some of the directions Navi and Kaepora Gaebora give, back then, they were relevant to any player starting the game. Another thing that required adapting to was that weapons in a 3D game required a lot more precision. Also, having familiarity with traditional Zelda puzzles, such as a block puzzle, wasn’t necessarily a help, because the experience of solving a block puzzle in 3D like the one in the Forest Temple is a lot different than solving one from A Link to the Past’s top-down perspective.

But as new games are released and the disparity between the skill level of new players and veterans increases, how do designers attempt to bridge this gap? One is by using “helpers”, which have become a staple in the main series since Ocarina of Time, though to mixed reception. Helpers began as the fairies Navi and Tatl, but have branched out to be characters such as talking boats (The Wind Waker), talking hats (The Minish Cap), mysterious imps (Twilight Princess), and even disembodied princesses (Spirit Tracks). Since Navi, they’ve slowly gained their own story and prominence in each game, but their primary function is the same: to provide guidance to the player. They are useful to young or inexperienced players, but too much involuntary involvement from them can frustrate veterans of the series.

One way that game designers attempt to straddle both skill sets is by having helpers offer advice when you are stuck on a puzzle, but only after several seconds of player inactivity. They will also sometimes offer help before this, if asked. Personally, I feel that one way this could be improved is to have an option in the main menu to turn guided hints on or off. Experienced players – or those who are replaying a game – could play without these hints for more challenge, while the option to turn them on maintains the traditional function of the helper.

One way that game designers attempt to straddle both skill sets is by having helpers offer advice when you are stuck on a puzzle, but only after several seconds of player inactivity. They will also sometimes offer help before this, if asked. Personally, I feel that one way this could be improved is to have an option in the main menu to turn guided hints on or off. Experienced players – or those who are replaying a game – could play without these hints for more challenge, while the option to turn them on maintains the traditional function of the helper.

Another way designers cater to different audiences is in level progression. This is not as simple as starting a game easier than it ends. A game that is too easy in the beginning may cause experienced players to lose interest; too hard, and new gamers could potentially grow discouraged and quit. The Wind Waker had a unique take on this: its opening “dungeon”, the Forsaken Fortress, was almost entirely stealth. This meant its main challenge involved timing and observation, key elements of Zelda puzzle solving. Not only did this begin to acclimate the new player to future puzzles, but it kept the dungeon from feeling like a “retread” for older gamers by de-emphasizing swordplay and enemy familiarization.

The Wind Waker, like many other games, did have a mandatory tutorial sequence before this. In that game it was Outset Island; in Ocarina of Time, it was Kokiri Forest; and in Twilight Princess, it was Ordon Village and Faron Woods. These areas can be useful the first time playing a game, especially if there are new controls to get used to, but they also mean that the main quest is postponed longer. If I were to suggest an improvement, I would separate the tutorial from the main quest so that it is a standalone story that is still connected to the main one. On the disc, they could be chapters, like on a DVD. While I expect most people would play the tutorial at some point out of curiosity, and some might like to play it all the time due to the story, it would be an advantage to be able to skip it during replays when players do not need their hands held.

One element of game difficulty that has not yet been discussed is enemy difficulty. A common fan complaint is that Twilight Princess enemies never do more than one heart of damage. Compare this to Ocarina of Time’s Twinrova, in which a flaming attack can take off as many as seven-and-a-half hearts. Like level progression, enemies tend to get harder as the game moves forward. But there are other ways that enemy difficulty is balanced. One is to have more than one way to defeat an enemy. Again, Ocarina of Time is a good example. Several boss chambers, like the one belonging to Morpha, had “safe” areas, which boss attacks could not reach. Beginning players could run to those to fight the boss, while more experienced ones could fight from the center of the room (usually, the most vulnerable location). Dark Link is another example of offering graduated difficulty; using the Biggoron Sword, the Megaton Hammer, or even Din’s Fire made the fight easier, while using the Master Sword required actual strategy.

One element of game difficulty that has not yet been discussed is enemy difficulty. A common fan complaint is that Twilight Princess enemies never do more than one heart of damage. Compare this to Ocarina of Time’s Twinrova, in which a flaming attack can take off as many as seven-and-a-half hearts. Like level progression, enemies tend to get harder as the game moves forward. But there are other ways that enemy difficulty is balanced. One is to have more than one way to defeat an enemy. Again, Ocarina of Time is a good example. Several boss chambers, like the one belonging to Morpha, had “safe” areas, which boss attacks could not reach. Beginning players could run to those to fight the boss, while more experienced ones could fight from the center of the room (usually, the most vulnerable location). Dark Link is another example of offering graduated difficulty; using the Biggoron Sword, the Megaton Hammer, or even Din’s Fire made the fight easier, while using the Master Sword required actual strategy.

I’ve seen statements by players who would like to have another game released that has two quests, such as the original legend of Zelda had. Or, for a 3D example, the preorder gift for The Wind Waker was a disc that contained both the original Ocarina of Time and its Master Quest (a version that had redesigned dungeons, increasing the difficulty). While I doubt any Zelda fan would turn down a game with two quests, there are still less labor-intensive ways to vary the game, and one of those ways would be to have a setting that changes the difficulty of the enemies the player faces. This does not just involve the level of damage dealt or taken, though that could be a factor. It means changing the enemies’ intelligence, such as how it reacts to the environment around it – for example, growing more cunning or aggressive if Link has low health.

The Zelda series also has another challenge in game design, though this one is story-related. Simply by virtue of it being a longstanding series, each player will have varying knowledge of Zelda lore. The key to writing the story so it appeals to both audiences is to have layers. These can range from “Easter Eggs” to obvious allusions to timeline placement. The Howling Stones in Twilight Princess may be interesting to new players, but they would not recognize the familiar songs like veterans would. The Hero’s Shade is just a mysterious character to those who are unfamiliar with previous “Chosen Heroes”, but provides a great subject for theorizing to those who are. The Wind Waker’s mid-story twist of discovering an entire kingdom underwater will be impressive to any player, but it will have the greatest impact for those who grew up on the Zelda series. And the entire game of Majora’s Mask can stand alone, but part of the fun for those who have played Ocarina of Time is recognizing how each character has been reused.

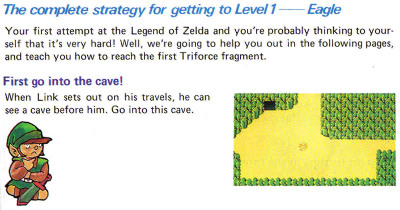

One help to both difficulty and story that has been underused lately is the game manual. Due to the limitations of video game systems when the original Legend of Zelda was released, there isn’t much of an in-game story to follow, but the manual explained the adventure, and even introduced the character of Impa. It has an items list, a bestiary, and walkthrough through the first dungeon. A Link to the Past’s manual, too, had a wealth of Zelda history. With the progression of the series, each game was able to become more self-contained in terms of story, while its game play and walkthroughs went in the opposite direction and can now be found in official guides instead of official manuals. Still, contrast the story section in Twilight Princess’ manual with the ones that came before: it is simply a summary of the game’s first hour. The rest of the manual may be a convenient resource for beginners if they need a refresher on the controls, but it still does not contain anything that can’t be found in-game. In my opinion, the game manual should evolve beyond the beginning player so that it again contains “secrets for everybody.”

Going back to the original quote, “You can’t please everyone” – when a game series has millions of fans, there’s going to be a large degree of truth to that statement. At a certain point, the designers have to trust their instincts, step back, and create the game they’d like to play. Still, the series has evolved to where it is today because it isn’t afraid of innovation. Perhaps in a future game, there will be changes such as difficulty settings, or something even greater that we haven’t yet imagined. In the meantime, fans will continue to be their creative selves and construct difficulty settings of their own through things such as three-heart challenges or sword-less runs. Regardless of your preference, happy playing.